Pablo Escobar

Pablo Escobar | |

|---|---|

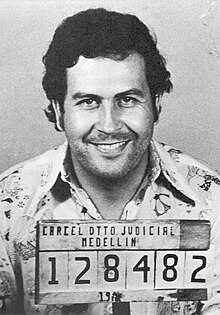

Escobar in a 1976 mugshot | |

| Born | Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria 1 December 1949 Rionegro, Colombia |

| Died | 2 December 1993 (aged 44) Medellín, Colombia |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound to the head |

| Resting place | Monte Sacro Cemetery |

| Spouse |

Maria Victoria Henao

(m. 1976) |

| Children |

|

| Other names |

|

| Organization | Medellín cartel |

| Conviction(s) | Illegal drug trade, assassinations, bombing, bribery, racketeering, murder |

| Criminal penalty | Five years' imprisonment |

| Signature | |

| |

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria (/ˈɛskəbɑːr/; Spanish: [ˈpaβlo eskoˈβaɾ]; 1 December 1949 – 2 December 1993) was a Colombian drug lord, narcoterrorist, and politician who was the founder and sole leader of the Medellín Cartel. Dubbed "the king of cocaine", Escobar was one of the wealthiest criminals in history, having amassed an estimated net worth of US$30 billion by the time of his death—equivalent to $70 billion as of 2022—while his drug cartel monopolized the cocaine trade into the United States in the 1980s and early 1990s.[1][2]

Born in Rionegro and raised in Medellín, Escobar studied briefly at Universidad Autónoma Latinoamericana of Medellín but left without graduating; he instead began engaging in criminal activity, selling illegal cigarettes and fake lottery tickets, as well as participating in motor vehicle theft. In the early 1970s, he began to work for various drug smugglers, often kidnapping and holding people for ransom.

In 1976, Escobar founded the Medellín Cartel, which distributed powder cocaine, and established the first smuggling routes from Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador, through Colombia and eventually into the United States. Escobar's infiltration into the U.S. created exponential demand for cocaine and by the 1980s it was estimated Escobar led monthly shipments of 70 to 80 tons of cocaine into the country from Colombia. As a result, he quickly became one of the richest people in the world,[1][3] but constantly battled rival cartels domestically and abroad, leading to massacres and the murders of police officers, judges, locals, and prominent politicians.[4]

In the 1982 Colombian parliamentary election, Escobar was elected as an alternate member of the Chamber of Representatives as part of the Liberal Party. Through this, he was responsible for community projects such as the construction of houses and football fields, which gained him popularity among the locals of the towns that he frequented; however, Escobar's political ambitions were thwarted by the Colombian and U.S. governments, who routinely pushed for his arrest, with Escobar widely believed to have orchestrated the Avianca Flight 203 and DAS Building bombings in retaliation.

In 1991, Escobar surrendered to authorities, and was sentenced to five years' imprisonment on a host of charges, but struck a deal of no extradition with Colombian President César Gaviria, with the ability of being housed in his own, self-built prison, La Catedral. In 1992, Escobar escaped and went into hiding when authorities attempted to move him to a more standard holding facility, leading to a nationwide manhunt.[5] As a result, the Medellín Cartel crumbled, and in 1993, Escobar was killed in his hometown by Colombian National Police, a day after his 44th birthday.[6]

Escobar's legacy remains controversial; while many denounce the heinous nature of his crimes, he was seen as a "Robin Hood-like" figure for many in Colombia, as he provided many amenities to the poor. His killing was mourned and his funeral attended by over 25,000 people.[7] Additionally, his private estate, Hacienda Nápoles, has been transformed into a theme park.[8] His life has also served as inspiration for or has been dramatized widely in film, television, and in music.

Early life

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born on 1 December 1949 in Rionegro, Antioquia Department. He belonged to the Paisa ethnic subgroup. His family was of Spanish origin, specifically from the Basque Country, and also had Italian roots.[9] He was the third of seven children and grew up in poverty, in the neighboring city of Medellín. His father was a small farmer and his mother was a teacher. Escobar left high school in 1966 just before his 17th birthday, before returning two years later with his cousin Gustavo Gaviria. At this time, the hard life on the streets of Medellín had polished them into gangster bullies in the eyes of teachers. The two dropped out of school after more than a year, but Escobar did not give up. Having forged a high school diploma, he studied briefly in college with the goal of becoming a criminal lawyer, a politician, and eventually the president but had to give up because of lack of money.[10][11][12][13]

Criminal career

Early

Escobar started his criminal career with his gang by stealing tombstones, sandblasting their inscriptions, and reselling them. After dropping out of school, Escobar began to join gangs to steal cars.[14] Escobar soon became involved in violent crime, employing criminals to kidnap people who owed him money and demand ransoms, sometimes tearing up ransom notes even when Escobar had received the ransom. His most famous kidnapping victim was businessman Diego Echavarria, who was kidnapped and eventually killed in the summer of 1971, Escobar received a $50,000 ransom from the Echavarria family; his gang became well known for this kidnapping.[15]

Medellín Cartel

Escobar had been involved in organized crime for a decade when the cocaine trade began to spread in Colombia in the mid-1970s. Escobar's meteoric rise caught the attention of the Colombian Security Service (DAS), who arrested him in May 1976 on his return from drug trafficking in Ecuador. DAS agents found 39 kg of cocaine in the spare tire of Escobar's car. Escobar managed to change the first judge in the lawsuit and bribed the second judge, so he was released along with other prisoners. The following year, the agent who arrested Escobar was assassinated. Escobar continued to bribe and intimidate Colombian law enforcement agencies in the same fashion. His carrot-and-stick strategy of bribing public officials and political candidates in Colombia, in addition to sending hitmen to murder the ones who rejected his bribes, came to be known as "silver or lead", meaning "money or death".[16][12][17] The Medellín Cartel and the Cali Cartel both managed to bribe Colombian politicians, and campaigned for both the Conservative and Liberal parties.[18][19] Hence, Escobar and many other Colombian drug lords were pulling strings in every level of the Colombian government because many of the political candidates whom they backed financially were eventually elected.[18] Although the Medellín Cartel was only established in the early 1970s, it expanded after Escobar met several drug lords on a farm in April 1978, and by the end of 1978 they had transported some 19,000 kilograms of cocaine to the United States.[20]

Rise to prominence

Soon, the demand for cocaine greatly increased in the United States, which led to Escobar organizing more smuggling shipments, routes, and distribution networks in South Florida, California, Puerto Rico, and other parts of the country. He and cartel co-founder Carlos Lehder worked together to develop a new trans-shipment point in the Bahamas, an island called Norman's Cay about 350 km (220 mi) southeast of the Florida coast. Escobar and Robert Vesco purchased most of the land on the island, which included a 1-kilometre (3,300 ft) airstrip, a harbor, a hotel, houses, boats, and aircraft, and they built a refrigerated warehouse to store the cocaine. According to his brother, Escobar did not purchase Norman's Cay; it was instead a sole venture of Lehder's. From 1978 to 1982, this was used as a central smuggling route for the Medellín Cartel. With the enormous profits generated by this route, Escobar was soon able to purchase 20 square kilometres (7.7 sq mi) of land in Antioquia for several million dollars, on which he built the Hacienda Nápoles. The luxury house he created contained a zoo, a lake, a sculpture garden, a private bullring, and other amenities for his family and the cartel.[21]

Escobar at the height of his power

At the height of his power, Escobar was involved in philanthropy in Colombia and paid handsomely for the staff of his cocaine lab. Escobar spent millions developing some of Medellín's poorest neighborhoods. He built housing complexes, parks, football stadiums, hospitals, schools, and churches.[22][23] Escobar also entered politics in the 1980s and participated in and supported the formation of the Liberal Party of Colombia. In 1982, he successfully entered the Colombian Congress. Although only an alternate, he was automatically granted parliamentary immunity and the right to a diplomatic passport under Colombian law. At the same time, Escobar was gradually becoming a public figure, and because of his charitable work, he was known as "Robin Hood Paisa". He alleged once in an interview that his fortune came from a bicycle rental company he founded when he was 16 years old.[24]

In Congress, the new Minister of Justice, Rodrigo Lara-Bonilla, had become Escobar's opponent, accusing Escobar of criminal activity from the first day of Congress. Escobar's arrest in 1976 was investigated by Lara-Bonilla's subordinates. A few months later, Liberal leader Luis Carlos Galán expelled Escobar from the party. Although Escobar fought back, he announced his retirement from politics in January 1984. Three months later, Lara-Bonilla was murdered.[25]

The Colombian judiciary had been a target of Escobar throughout the mid-1980s. While bribing and murdering several judges, in the fall of 1985, the wanted Escobar requested the Colombian government to allow his conditional surrender without extradition to the United States. The proposal was initially rejected, and Escobar subsequently founded and implicitly supported the Los Extraditable Organization, which aims to fight extradition policy. The Los Extraditable Organization was subsequently accused of participating in an effort to prevent the Colombian Supreme Court from studying the constitutionality of Colombia's extradition treaty with the United States. It supported the far-left guerrilla movement that attacked the Colombian Judiciary Building and killed half of the justices of the Supreme Court on 6 November 1985. In late 1986, Colombia's Supreme Court declared the previous extradition treaty illegal due to being signed by a presidential delegation, not the president. Escobar's victory over the judiciary was short-lived, with new president Virgilio Barco Vargas having quickly renewed his agreement with the United States.[26][27]

Escobar still held a grudge against Luis Carlos Galán for kicking him out of politics, so Galán was assassinated on 18 August 1989 at Escobar's orders. Escobar then planted a bomb on Avianca Flight 203 in an attempt to assassinate Galán's successor, César Gaviria Trujillo, who missed the plane and survived. All 107 people were killed in the blast. Because two Americans were also killed in the bombing, the U.S. government began to intervene directly.[28][29]

La Catedral prison

After the assassination of Luis Carlos Galán, the administration of César Gaviria moved against Escobar and the drug cartels. Eventually, the government negotiated with Escobar and convinced him to surrender and cease all criminal activity in exchange for a reduced sentence and preferential treatment during his captivity. Declaring an end to a series of previous violent acts meant to pressure authorities and public opinion, Escobar surrendered to Colombian authorities in 1991. Before he gave himself up, the extradition of Colombian citizens to the United States had been prohibited by the newly approved Colombian Constitution of 1991. This act was controversial, as it was suspected that Escobar and other drug lords had influenced members of the Constituent Assembly in passing the law. Escobar was confined in what became his own luxurious private prison, La Catedral, which featured a football pitch, a giant dollhouse, a bar, a Jacuzzi, and a waterfall. Accounts of Escobar's continued criminal activities while in prison began to surface in the media, which prompted the government to attempt to move him to a more conventional jail on 22 July 1992. Escobar's influence allowed him to discover the plan in advance and make a successful escape, spending the remainder of his life evading the police.[30][31]

Death

Escobar faced threats from the Colombian police, the U.S. government and his rivals, the Cali Cartel. On 2 December 1993, Escobar was found in a house in a middle-class residential area of Medellín by Colombian special forces, using technology provided by the United States which allowed them to trace Escobar's location after he made a call to his family. Police tried to arrest Escobar but the situation quickly escalated to an exchange of gunfire. Escobar was shot and killed while trying to escape from the roof, along with a bodyguard who was also shot. He was hit by bullets in the torso and feet, and a bullet which struck him in the head, killing him. This sparked debate about whether he killed himself or whether he was shot and killed.[12]

Aftermath of his death

Soon after Escobar's death and the subsequent fragmentation of the Medellín Cartel, the cocaine market became dominated by the rival Cali Cartel until the mid-1990s when its leaders were either killed or captured by the Colombian government. The Robin Hood image that Escobar had cultivated maintained a lasting influence in Medellín. Many there, especially many of the city's poor whom Escobar had aided while he was alive, mourned his death, and over 25,000 people attended his funeral. Some of them consider him a saint and pray to him for receiving divine help. Escobar was buried at the Monte Sacro Cemetery.[32]

Virginia Vallejo's testimony

On 4 July 2006, Virginia Vallejo, a television anchorwoman romantically involved with Escobar from 1983 to 1987, offered Attorney General Mario Iguarán her testimony in the trial against former Senator Alberto Santofimio, who was accused of conspiracy in the 1989 assassination of presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán. Iguarán acknowledged that, although Vallejo had contacted his office on 4 July, the judge had decided to close the trial on 9 July, several weeks before the prospective closing date. The action was seen as too late.[33][34]

On 18 July 2006, Vallejo was taken to the United States on a special flight of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) for "safety and security reasons" due to her cooperation in high-profile criminal cases.[35][36] On 24 July, a video in which Vallejo had accused Santofimio of instigating Escobar to eliminate presidential candidate Galán was aired by RCN Television of Colombia. The video was seen by 14 million people, and was instrumental for the reopened case of Galán's assassination. On 31 August 2011 Santofimio was sentenced to 24 years in prison for his role in the crime.[37][38]

Role in the Palace of Justice siege

Among Escobar's biographers, only Vallejo has given a detailed explanation of his role in the 1985 Palace of Justice siege. She stated that Escobar had financed the operation, which was committed by M-19; she blamed the army for the killings of more than 100 people, including 11 Supreme Court magistrates, M-19 members, and employees of the cafeteria. Her statements prompted the reopening of the case in 2008; Vallejo was asked to testify, and many of the events she had described in her book and testimonial were confirmed by Colombia's Commission of Truth.[39][40] These events led to further investigation into the siege that resulted with the conviction of a high-ranking former colonel and a former general, later sentenced to 30 and 35 years in prison, respectively, for the forced disappearance of the detained after the siege.[41][42] Vallejo would subsequently testify in Galán's assassination.[43] In her book, Amando a Pablo, odiando a Escobar (Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar), she had accused several politicians, including Colombian presidents Alfonso López Michelsen, Ernesto Samper, and Álvaro Uribe of having links to drug cartels.[44]

Relatives

Escobar's widow (María Henao, now María Isabel Santos Caballero), son (Juan Pablo, now Sebastián Marroquín Santos) and daughter (Manuela) fled Colombia in 1995 after failing to find a country that would grant them asylum.[45] Despite Escobar's numerous and continual infidelities, Maria remained supportive of her husband. Members of the Cali Cartel even replayed their recordings of her conversations with Pablo for their wives to demonstrate how a woman should behave.[46] This attitude proved to be the reason the cartel did not kill her and her children after Pablo's death, although the group demanded and received millions of dollars in reparations for Escobar's war against them. Henao even successfully negotiated for her son's life by personally guaranteeing he would not seek revenge against the cartel or participate in the drug trade.[47]

After escaping first to Mozambique, then to Brazil, the family settled in Argentina.[48] Living under her assumed name, Henao became a successful real estate entrepreneur until one of her business associates discovered her true identity, and Henao absconded with her earnings. Local media were alerted, and after being exposed as Escobar's widow, Henao was imprisoned for eighteen months while her finances were investigated. Ultimately, authorities were unable to link her funds to illegal activity, and she was released.[49] According to her son, Henao fell in love with Escobar "because of his naughty smile [and] the way he looked at [her]. [He] was affectionate and sweet. A great lover. I fell in love with his desire to help people and his compassion for their hardship. We [would] drive to places where he dreamed of building schools for the poor. From [the] beginning, he was always a gentleman."[50] María Victoria Henao de Escobar, with her new identity as María Isabel Santos Caballero, continues to live in Buenos Aires with her son and daughter.[51] On 5 June 2018, the Argentine federal judge Nestor Barral accused her and her son, Sebastián Marroquín Santos, of money laundering with two Colombian drug traffickers.[52][53][54] The judge ordered the seizing of assets for about $1m each.[55]

Argentinian filmmaker Nicolas Entel's documentary Sins of My Father (2009) chronicles Marroquín's efforts to seek forgiveness, on behalf of his father, from the sons of Rodrigo Lara, Colombia's justice minister who was assassinated in 1984, as well as from the sons of Luis Carlos Galán, the presidential candidate who was assassinated in 1989. The film was shown at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival and premiered in the U.S. on HBO in October 2010.[56] In 2014, Marroquín published Pablo Escobar, My Father under his birth name. The book provides a firsthand insight into details of his father's life and describes the fundamentally disintegrating effect of his death upon the family. Marroquín aimed to publish the book in hopes to resolve any inaccuracies regarding his father's excursions during the 1990s.[57]

Escobar's sister, Luz Maria Escobar, made multiple gestures in attempts to make amends for the drug baron's crimes. These include making public statements in the press, leaving letters on the graves of his victims, and, on the 20th anniversary of his death, organizing a public memorial for his victims.[58] Escobar's body was exhumed on 28 October 2006 at the request of some of his relatives in order to take a DNA sample to confirm the alleged paternity of an illegitimate child and remove all doubt about the identity of the body that had been buried next to his parents for 12 years.[59] A video of the exhumation was broadcast by RCN, angering Marroquín, who accused his uncle, Roberto Escobar, and cousin, Nicolas Escobar, of being "merchants of death" by allowing the video to air.[60]

Hacienda Nápoles

After Escobar's death, the ranch, zoo and citadel at Hacienda Nápoles were given by the government to low-income families under a law called Extinción de Dominio (Domain Extinction). The property has been converted into a theme park surrounded by four luxury hotels overlooking the zoo.[61]

Escobar Inc

In 2014, Roberto Escobar founded Escobar Inc with Olof K. Gustafsson and registered Successor-In-Interest rights for his brother Pablo Escobar in California, United States.[62]

Hippos

Escobar kept four hippos in a private menagerie at Hacienda Nápoles. They were deemed too difficult to seize and move after Escobar's death, and hence left on the untended estate. By 2007, the animals had multiplied to 16 and had taken to roaming the area for food in the nearby Magdalena River.[63][64] In 2009, two adults and one calf escaped the herd and, after attacking humans and killing cattle, one of the adults (called "Pepe") was killed by hunters under authorization of the local authorities.[64] As of early 2014, 40 hippos have been reported to exist in Puerto Triunfo, Antioquia Department, from the original four belonging to Escobar.[65] As of 2016, without management, the population size is likely to more than double in the next decade.[66]

The National Geographic Channel produced a documentary about them titled Cocaine Hippos.[67] A report published in a Yale student magazine noted that local environmentalists are campaigning to protect the animals, although there is no clear plan for what will happen to them.[68] In 2018, National Geographic published another article on the hippos which found disagreement among environmentalists on whether they were having a positive or negative impact but that conservationists and locals – particularly those in the tourism industry – were mostly in support of their continued presence.[69] By October 2021, the Colombian government had started a program of chemically sterilizing the animals.[70]

Apartment demolition

On 22 February 2019, at 11:53 AM local time, Medellín authorities demolished the six-story Edificio Mónaco apartment complex in the El Poblado neighborhood where, according to retired Colombian general Rosso José Serrano, Escobar planned some of his most brazen attacks. The building was initially built for Escobar's wife but was gutted by a Cali Cartel car bomb in 1988 and had remained unoccupied ever since, becoming an attraction to foreign tourists seeking out Escobar's physical legacy. Mayor Federico Gutierrez had been pushing to raze the building and erect in its place a park honoring the thousands of cartel victims, including four presidential candidates and some 500 police officers. Colombian President Ivan Duque said the demolition "means that history is not going to be written in terms of the perpetrators, but by recognizing the victims", hoping the demolition would showcase that the city had evolved significantly and had more to offer than the legacy left by the cartels.[71]

Personal life

Family and relationships

In March 1976, the 26-year-old Escobar married María Victoria Henao, who was 15. The relationship was discouraged by the Henao family, who considered Escobar socially inferior; the pair eloped.[72] They had two children: Juan Pablo (now Sebastián Marroquín) and Manuela. In 2007, the journalist Virginia Vallejo published her memoir Amando a Pablo, odiando a Escobar (Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar), in which she describes her romantic relationship with Escobar and the links of her lover with several presidents, Caribbean dictators, and high-profile politicians.[73] Her book inspired the movie Loving Pablo (2017).[74] A drug distributor, Griselda Blanco, is also reported to have conducted a clandestine but passionate relationship with Escobar; several items in her diary link him with the nicknames "Coque de Mi Rey" (My Coke King) and "Polla Blanca" (White Cock).[75]

Properties

After becoming wealthy, Escobar created or bought numerous residences and safe houses, with the Hacienda Nápoles gaining significant notoriety. The luxury house contained a colonial house, a sculpture park, and a complete zoo with animals from various continents, including elephants, exotic birds, giraffes, and hippopotamuses. Escobar had also planned to construct a Greek-style citadel near it, and though construction of the citadel was started, it was never finished.[61]

Escobar owned a home in the US under his own name: a 6,500 square foot (604 m2), pink, waterfront mansion situated at 5860 North Bay Road in Miami Beach, Florida. The four-bedroom estate, built in 1948 on Biscayne Bay, was seized by the US federal government in the 1980s. Later, the dilapidated property was owned by Christian de Berdouare, proprietor of the Chicken Kitchen fast-food chain, who had bought it in 2014. De Berdouare would later hire a documentary film crew and professional treasure hunters to search the edifice before and after demolition, for anything related to Escobar or his cartel. They would find unusual holes in floors and walls, as well as a safe that was stolen from its hole in the marble flooring before it could be properly examined.[76]

Escobar owned a huge Caribbean getaway on Isla Grande, the largest of the cluster of the 27 coral cluster islands comprising Islas del Rosario, located about 35 km (22 mi) from Cartagena. The compound, now half-demolished and overtaken by vegetation and wild animals, featured a mansion, apartments, courtyards, a large swimming pool, a helicopter landing pad, reinforced windows, tiled floors, and a large but unfinished building to the side of the mansion.[77]

In popular culture

Books

Escobar has been the subject of several books, including the following:

- Escobar (2010), by Roberto Escobar, written by his brother shows how he became infamous and ultimately died.[78]

- Escobar Gaviria, Roberto (2016). My Brother – Pablo Escobar. Escobar, Inc. ISBN 978-0692706374.

- Kings of Cocaine (1989), by Guy Gugliotta, retells the history and operations of the Medellín Cartel, and Escobar's role within it.[79]

- Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World's Greatest Outlaw (2001), by Mark Bowden,[80][81] relates how Escobar was killed and his cartel dismantled by U.S. special forces and intelligence, the Colombian military, and Los Pepes.[82]

- Pablo Escobar: My Father (2016), by Juan Pablo Escobar, translated by Andrea Rosenberg.[83]

- Pablo Escobar: Beyond Narcos (2016), by Shaun Attwood, tells the story of Escobar and the Medellín Cartel in the context of the failed War on Drugs; ISBN 978-1537296302

- Manhunters: How We Took Down Pablo Escobar (2019), by Stephen Murphy and Javier F. Peña, former DEA agents on the hunt for Pablo Escobar in the 1990s. [84]

- American Made: Who Killed Barry Seal? Pablo Escobar or George HW Bush (2016), by Shaun Attwood, tells Pablo's story as a suspect in the murder of CIA pilot Barry Seal; ISBN 978-1537637198

- Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar (2017) by Virginia Vallejo, originally published by Penguin Random House in Spanish in 2007, and later translated to 16 languages.

- News of a Kidnapping, (original Spanish title: Noticia de un secuestro) non-fiction 1996 book by Gabriel García Márquez, and published in English in 1997.

Films

Two major feature films on Escobar, Escobar (2009) and Killing Pablo (2011), were announced in 2007.[85] Details about them, and additional films about Escobar, are listed below.

- Blow, a 2001 American biographical film based on George Jung, a member of the Medellín Cartel; Escobar was portrayed by Cliff Curtis.

- Pablo Escobar: The King of Coke (2007) is a TV movie documentary by National Geographic, featuring archival footage and commentary by stakeholders.[86][87]

- Escobar (2009) was delayed because of producer Oliver Stone's involvement with the George W. Bush biopic W. (2008). As of 2008, the release date of Escobar remained unconfirmed.[when?][88] Regarding the film, Stone said: "This is a great project about a fascinating man who took on the system. I think I have to thank Scarface, and maybe even Ari Gold."[89]

- Killing Pablo (2011) was supposedly in development for several years, directed by Joe Carnahan. It was to be based on Mark Bowden's 2001 book of the same title, which in turn was based on his 31-part Philadelphia Inquirer series of articles on the subject.[81][82] The cast was reported to include Christian Bale as Major Steve Jacoby and Venezuelan actor Édgar Ramírez as Escobar.[90][91] In December 2008, Bob Yari, producer of Killing Pablo, filed for bankruptcy.[92]

- Escobar: Paradise Lost (2014) a romantic thriller in which a naive Canadian surfer falls in love with a girl who turns out to be Escobar's niece.

- Loving Pablo (2017), Spanish film based on Virginia Vallejo's book Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar with Javier Bardem as Escobar, and Penélope Cruz as Virginia Vallejo.[93]

- American Made (2017), American action-comedy film loosely based on the life of Barry Seal; Escobar was portrayed by Mauricio Mejía.[94]

- Weird: The Al Yankovic Story (2022), American biopic parody loosely based on the life of "Weird Al" Yankovic; Arturo Castro portrays Escobar who is depicted as a Weird Al fan who kidnaps Weird Al's girlfriend, Madonna, to lure him to play at his fortieth birthday party. Weird Al instead murders him.

Television

- In 2005, Court TV (now TruTV) crime documentary series Mugshots released an episode on Escobar titled "Pablo Escobar – Hunting The Druglord".[95]

- In the 2007 HBO television series, Entourage, actor Vincent Chase (played by Adrian Grenier) is cast as Escobar in a fictional film entitled Medellín.[96]

- One of ESPN's 30 for 30 series films, The Two Escobars (2010), by directors Jeff and Michael Zimbalist, looks back at Colombia's World Cup run in 1994 and the relationship between sports and the country's criminal gangs — notably the Medellín narcotics cartel run by Escobar. The other Escobar in the film title refers to former Colombian defender Andrés Escobar (no relation to Pablo), who was shot and killed one month after conceding an own goal that contributed to the elimination of the Colombian national team from the 1994 FIFA World Cup.[97]

- Caracol TV produced a television series, El cartel (The Cartel), which began airing on 4 June 2008 where Escobar is portrayed by an unknown model when he is shot down by Cartel del Sur's hitmen.

- Also Caracol TV produced a TV Series, Pablo Escobar: El Patrón del Mal (Pablo Escobar, The Boss of Evil), which began airing on 28 May 2012, and stars Andrés Parra as Pablo Escobar. It is based on Alonso Salazar's book La parábola de Pablo.[98] Parra reprises his role in TV series Football Dreams, A World of Passion and in the first season of El Señor de los Cielos. Parra has declared not to play the character again so as not to typecast himself.

- RTI Producciones produced a TV Series for RCN Televisión, Tres Caínes, was released on 4 March 2013, which Escobar is portrayed by the Colombian actor Juan Pablo Franco (who portrayed general Muriel Peraza in Pablo Escobar: El Patrón del Mal) in the first phase of the series. Franco reprises his role in Surviving Escobar: Alias JJ.

- Also in 2013, Fox Telecolombia produced for RCN Televisión a TV Series, Alias El Mexicano, released on 5 November 2013, which Escobar is portrayed by an unknown actor in a minor role.

- A Netflix original television series depicting the story of Escobar, titled Narcos, was released on 28 August 2015, starring Brazilian actor Wagner Moura as Pablo.[99] Season two premiered on the streaming service on 2 September 2016.[100]

- In 2016, Teleset and Sony Pictures Television produced for RCN Televisión the TV Series En la boca del lobo, was released on 16 August 2016, which Escobar is portrayed by Fabio Restrepo (who portrayed Javier Ortiz in Pablo Escobar: El Patrón del Mal) as the character of Flavio Escolar.

- National Geographic in 2016 broadcast a biography series Facing that included an episode featuring Escobar.[101]

- On 24 January 2018, Netflix released the 68-minute-long documentary Countdown to Death: Pablo Escobar directed by Santiago Diaz and Pablo Martin Farina.[102][103]

- Killing Escobar was a documentary televised in the UK in 2021. It concerned a failed attempt by mercenaries, contracted by the Cali Cartel and led by Peter McAleese, to assassinate Escobar in 1989.

- Fox Telecolombia produced in 2019 a TV Series, El General Naranjo, which aired on 24 May 2019, which Escobar is portrayed by the Colombian actor Federico Rivera.

Music

- The 2013 song "Pablo" by American rapper E-40 serves as an ode to the legacy of Pablo Escobar.[104]

- The 2016 album The Life of Pablo by American rapper Kanye West was named after the three Pablos who inspired and represented some part of the album, with one of them being Pablo Escobar.[105]

- Dubdogz's "Pablo Escobar" (feat. Charlott Boss), released in 2020, has garnered more than 5.6 million views for its official music video.[106]

- The 2018 hit single Narcos by the Atlanta-based rap group Migos from their album Culture II makes references to Pablo Escobar as well as the Medellin Cartel, and the Netflix series Narcos.[107]

References

- ^ a b Macias, Amanda (21 September 2015). "10 facts reveal the absurdity of Pablo Escobar's wealth". businessinsider.com. Insider Inc. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ "Here's How Rich Pablo Escobar Would Be If He Was Alive Today". UNILAD. 13 September 2016. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ Escobar, Juan Pablo (2014). Pablo Escobar, My Father. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 469.

- ^ "Pablo Escobar Gaviria – English Biography – Articles and Notes". ColombiaLink.com. Archived from the original on 8 November 2006. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ "Familiares exhumaron cadáver de Pablo Escobar para verificar plenamente su identidad". El Tiempo.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Decline of the Medellín Cartel and the Rise of the Cali Mafia". U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Archived from the original on 18 January 2006. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ "Pablo Escobar: Biography". Biography.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ "Escobar's Former Mansion Will Now Be A Theme Park". Medellín Living. 13 January 2014. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ cuatro.com (19 April 2018). "Roberto, hermano de Pablo Escobar: "Mi familia tiene raíces españolas, del País Vasco"". Cuatro (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ "Pablo Escobar: The Rise and Fall of the 'King of Cocaine'". Archived from the original on 15 February 2024. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Deas, Malcolm (4 December 1993). "Obituary: Pablo Escobar". Independent. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Minster, Christopher (8 July 2016). "Biography of Pablo Escobar". About.com. About, Inc. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Chepesiuk, Ron (2013). Escobar Versus Cali: The War of the Cartels. Strategic Media Books. ISBN 9781939521019.

- ^ Escobar, Roberto (2012). Escobar. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1848942912. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ Bowden, Mark (2001). Killing Pablo. London: Atlantic Books. pp. 33–37. ISBN 978-1-84354-651-1. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Torres, Rubén Ortiz (9 February 2020). "Plata O Plomo O Glitter". royaleprojects.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Bowden 2001, pp. 40–42.

- ^ a b Rubio, Mauricio. "Colombia: Coexistence, Legal Confrontation, and War with Illegal Armed Groups" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2021.

- ^ Collett, Merrill (14 November 1987). "COLOMBIA'S DRUG LORDS WAGING WAR ON LEFTISTS". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ Chepsiuk, Ron (1999). The War on Drugs: An International Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-87436-985-4. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "The godfather of cocaine". Frontline. WGBH. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ "Pablo Escobar: Interesting Facts You May Not Know About the King of Cocaine". LATIN POST. 25 October 2020. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ Herzog, Rudolph (9 July 2015). "Pablo Escobar Biopic: The Cocaine King Full of Contradictions". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ Bowden 2001, pp. 48–57.

- ^ Bowden 2001, pp. 63–67.

- ^ "Cali Colombia Nacional Pablo Escobar financió la toma del Palacio de Justicia Escobar financió toma del Palacio de Justicia". El Pais. Archived from the original on 24 October 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ Bowden 2001, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Bowden 2001, pp. 93–94.

- ^ "25 years on, Colombia still mourns Escobar plane bombing, still wants answers". The Japan Times. 8 July 2016. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Treaster, Joseph B. (23 July 1992). "Colombian Drug Baron Escapes Luxurious Prison After Gunfight". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ Ross, Timothy (24 July 1992). "Escobar escape humiliates Colombian leaders". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2017 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Wallace, Arturo (2 December 2013). "Drug boss Pablo Escobar still divides Colombia". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Colombian Attorney General on Virginia Vallejo's offer to testify against Santofimio" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2011.

- ^ "Back to jail for Colombia ex-minister". Independent Online. Bogotá. 1 September 2011. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ "Virginia Vallejo takes refuge in United States". Virginia Vallejo. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. reprinted and translated from Gonzalo Guillen (16 July 2006). "Virginia Vallejo". El Nuevo Herald.

- ^ "Pablo Escobar's Ex-Lover Flees Colombia". Fox News Channel. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- ^ "Testimony of Virginia Vallejo in 2006". Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Radio Nizkor: Colombia". www.radionizkor.org. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Virginia Vallejo testificó en el caso Palacio de Justicia". Caracol Radio. 27 August 2008. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ Michael Evans (17 December 2009). "Truth Commission Blames Colombian State for Palace of Justice Tragedy". UNREDACTED. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ "Colombia ex-officer jailed after historic conviction". BBC News. 10 June 2010. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Colombian 1985 Supreme Court raid commander sentenced". BBC News. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Galan Slaying a State Crime, Colombian Prosecutors Say". Latin American Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ Romero, Simon (3 October 2007). "Colombian Leader Disputes Claim of Tie to Cocaine Kingpin". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ "Drug lord's wife and son arrested". BBC News. 17 November 1999. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ Escobar 2014, p. 466.

- ^ Escobar 2014, pp. 468–495.

- ^ King, Julie (15 June 2015). "A Cursed Family: A Look at Pablo Escobar's Family 21 Years After His Death". XPat Nation. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016.

- ^ Escobar 2014, pp. 521–537.

- ^ Escobar 2014, p. 68.

- ^ "Se conoce foto de la hija de Pablo Escobar en Buenos Aires". El Tiempo. 25 April 2018. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ "Pablo Escobar's widow and son in Argentina money laundering probe". Deutsche Welle. 1 November 2017. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ "Pablo Escobar's widow and son held on money laundering charges in Argentina". 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ Lam, Katherine (6 June 2018). "Pablo Escobar's widow, son charged with money laundering in Argentina". Fox News. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ "Pablo Escobar's widow and son held on money laundering charges in Argentina". The Guardian. 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ "Drug lord's son seeks forgiveness". CNN. 12 December 2009. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ Shepherd, Jack (12 September 2016). "Narcos season 2: Pablo Escobar's son labels Netflix show 'insulting', lists 28 historical errors". Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022.

- ^ Alexander, Harriet (3 December 2014). "Pablo Escobar's sister trying to pay for the sins of her brother (Luz Maria Escobar), the sister of Colombian cartel boss Pablo Escobar, has told how she is trying to make amends for her murderous brother". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Familiares exhumaron cadáver de Pablo Escobar para verificar plenamente su identidad". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ "La exhumación de Pablo". Semana (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ a b Ceaser, Mike (2 June 2008). "At home on Pablo Escobar's ranch". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ "California Business Portal: Successor-In-Interest". 28 April 2015. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ Kraul, Chris (20 December 2006). "A hippo critical situation". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- ^ a b "Colombia kills drug baron hippo". BBC News. 11 July 2009. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ^ "Hipopótamos bravos". El Espectador. 24 June 2014. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014. English translation Archived 21 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine at Google Translate

- ^ Howard, B.C. (10 May 2016). "Pablo Escobar's Escaped Hippos Are Thriving in Colombia". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ "The Invaders: Cocaine Hippos". National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on 26 June 2013.

- ^ Nagvekar, Rahul (8 March 2017). "Zoo Gone Wild: After Escobar, Colombia Faces His Hippos". The Politic. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ Wilcox, Christie (26 September 2018). "Could Pablo Escobar's Escaped Hippos Help the Environment?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ "Pablo Escobar: Colombia sterilises drug lord's hippos". BBC News. 16 October 2021. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Pablo Escobar's six-floor apartment demolished in Medellin as symbol of rebirth". Fox News. 22 February 2019. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Escobar 2014, p. 74.

- ^ "Los Narcopresidentes" [The Narco-presidents]. YouTube (in Spanish). 24 November 2008. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Mayorga, Emilio (3 September 2017). "Loving Pablo Director on Reuniting Javier Bardem and Penelope Cruz: It's Been Very Intense". Variety. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ Jerry, Tom (30 September 2013). "Me Matan, Limon! -Patricio Rey y sus Redonditos de Ricota". INEDITO. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Macias, Amanda (24 January 2016). "Military & Defense: A luxurious Miami mansion built by the 'King of Cocaine' is no more". Business Insider. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Macias, Amanda (12 May 2016). "Military & Defense: This dilapidated villa once served as a Caribbean getaway for drug-kingpin Pablo Escobar". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Escobar, Roberto (2010). Escobar. Hodder Paperbacks.

- ^ McAleese, Peter (1993). No Mean Soldier. Cassell Pub.

- ^ Bowden, Mark (2002). Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World's Greatest Outlaw. Penguin Pub.

- ^ a b McNary, Dave (1 October 2007). "Yari fast-tracking Escobar biopic". Variety. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- ^ a b "What is actor Christian Bale doing next?". Journal Now. 25 December 2008. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ Escobar, Juan Pablo (2016). Pablo Escobar: My Father. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 9781250104625.

- ^ "Manhunters: How We Took Down Pablo Escobar".Amazon website

- ^ "Weekly Screengrab: Sparring Partners". TribecaFilmFestival.org. 1 October 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Pablo Escobar: The King of Coke. National Geographic. 2007. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2016. (Amazon)

- ^ Pablo Escobar: The King of Coke. National Geographic. 2007. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2016. (La Peliculas)

- ^ "No Bardem for Killing Pablo". WhatCulture. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (8 October 2007). "Stone to produce another 'Escobar'". Variety. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- ^ "Venezuelan actor Edgar Ramirez to Play PABLO ESCOBAR". Poor But Happy. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009.

- ^ Faraci, Devin (14 August 2008). "Joe Carnahan Is Going to Be Killing a New Pablo, and We Know Who It Is". Chud. Archived from the original on 15 August 2008.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (12 December 2008). "Bob Yari crashes into Chapter 11". Variety.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (11 September 2017). "Javier Bardem on Playing Pablo Escobar With Penelope Cruz in Loving Pablo". Variety. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ "'American Made': Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ "Mugshots | Pablo Escobar – Hunting the Druglord". snagfilms.com. 2005. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

This episode follows Escobar on his journey to becoming the Columbian Godfather.

- ^ Barius, Claudette (18 June 2007). "Entourage: The making of Medellín". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ "The Two Escobars". the2escobars.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ "Telemundo Media's 'Pablo Escobar, El Patron del Mal' Averages Nearly 2.2 Million Total Viewersby zap2it.com". TV by the Numbers. Zap2It. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Shepherd, Jack (28 July 2015). "New on Netflix August 2015: From Narcos and Spellbound to Kick Ass 2 and Dinotrux". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Strause, Jackie (2 September 2016). "'Narcos' Season 2: Episode-by-Episode Binge-Watching Guide". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Sang, Lucia I. Suarez (30 August 2016). "Ex-DEA agents who fought Pablo Escobar headline new NatGeo documentary". Fox News. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "Countdown to Death: Pablo Escobar". Netflix.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Is Countdown to Death: Pablo Escobar (2017) on Netflix USA?". What's New on Netflix USA. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "E-40 – 'The Block Brochure Parts 4, 5 & 6' (Album Covers & Track Lists)". hiphop-n-more.com. 29 October 2013. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Trzcinski, Matthew (5 May 2020). "Kanye West Once Explained the Identity of Pablo From 'The Life of Pablo'". cheatsheet.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Dubdogz - Pablo Escobar (feat. Charlott Boss) [Official Music Video], 10 July 2020, retrieved 3 September 2022

- ^ "Migos - Narcos". Youtube. 27 June 2018. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

External links

![]() Media related to Pablo Escobar at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pablo Escobar at Wikimedia Commons

- "The Abandoned House of Pablo Escobar". noaccess.eu. Archived from the original on 2 September 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- Pablo Escobar at IMDb

- Pablo Escobar

- 1949 births

- 1993 deaths

- 20th-century criminals

- Colombian drug traffickers

- Colombian mass murderers

- Colombian crime bosses

- Medellín Cartel traffickers

- Folk saints

- Colombian people of Basque descent

- Colombian people of Italian descent

- Colombian Roman Catholics

- Members of the Chamber of Representatives of Colombia

- People from Rionegro

- People shot dead by law enforcement officers in Colombia

- Escobar Gaviria family