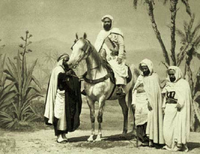

Emir Abdelkader

Abd al-Qadir al-Jaza'iri عـبـد الـقـادر الـجـزائـري | |

|---|---|

Photographed by Étienne Carjat in 1865 | |

| Native name | عبد القادر ابن محي الدين |

| Birth name | Abd al-Qadir ibn Muhyi al-Din al-Hassani |

| Born | 6 September 1808 Guetna, Regency of Algiers |

| Died | 26 May 1883 (aged 74) Damascus, Ottoman Syria[1] |

| Buried | |

| Rank | Emir |

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | Legion of Honour (Grand Cross) Order of Pius IX First Class of the Order of the Medjidie Order of the Redeemer (Grand Cross) |

Abd al-Qadir ibn Muhyi al-Din (6 September 1808 – 26 May 1883; Arabic: عبد القادر ابن محي الدين ʿAbd al-Qādir ibn Muḥy al-Dīn), known as the Emir Abdelkader or Abd al-Qadir al-Hassani al-Jaza'iri, was an Algerian religious and military leader who led a struggle against the French colonial invasion of Algiers in the early 19th century. As an Islamic scholar and Sufi who unexpectedly found himself leading a military campaign, he built up a collection of Algerian tribesmen that for many years successfully held out against one of the most advanced armies in Europe. His consistent regard for what would now be called human rights, especially as regards his Christian opponents, drew widespread admiration, and a crucial intervention to save the Christian community of Damascus from a massacre in 1860 brought honours and awards from around the world. Within Algeria, he was able to unite many Arab and Berber tribes to resist the spread of French colonization.[2] His efforts to unite the country against French invaders led some French authors to describe him as a "modern Jugurtha",[3] and his ability to combine religious and political authority has led to his being acclaimed as the "Saint among the Princes, the Prince among the Saints".[4]

Name

[edit]The name "Abdelkader" is sometimes transliterated as "ʻAbd al-Qādir", "Abd al-Kader", "Abdul Kader" or other variants, and he is often referred to as simply the Emir Abdelkader (since El Jezairi just means "the Algerian"). "Ibn Muhieddine" is a patronymic meaning "son of Muhieddine".

Early years

[edit]

Abdelkader was born in el Guetna, a town and commune in Mascara on September 6 1808,[5] to a religious family. His father, Muhieddine (or "Muhyi al-Din") al-Hasani, was a muqaddam in a religious institution affiliated with the Qadiriyya tariqa[6] and claimed descendence from Muhammad, through the Idrisid dynasty.[7] Abdelkader was thus a sharif, and entitled to add the honorary patronymic al-Hasani ("descendant of Hasan ibn Ali") to his name.[6]

He grew up in his father's zawiya, which by the early nineteenth century had become the centre of a thriving community on the banks of the Oued al-Hammam. Like other students, he received a traditional and common education in theology, jurisprudence and grammar; it was said that he could read and write by the age of five. A gifted student, Abdelkader succeeded in reciting the Qur'an by heart at the age of 14, thereby receiving the title of ḥāfiẓ; a year later, he went to Oran for further education.[6] He was a good orator and could excite his peers with poetry and religious diatribes.[1] He is noted for numerous published essays about adapting Islamic law to modern society.[8]

As a young man In 1825, he set out on the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, with his father. While there, he encountered Imam Shamil; the two spoke at length on different topics. He also traveled to Damascus and Baghdad, and visited the graves of noted Muslims, such as ibn Arabi and Abdul Qadir Gilani, who was also called al-Jilālī in Algeria. This experience cemented his religious enthusiasm. On his way back to Algeria, he was impressed by the reforms carried out by Muhammad Ali of Egypt.[9] He returned to his homeland a few months before the arrival of the French under the July Monarchy.

French invasion and resistance

[edit]| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

Early success (1830–1837)

[edit]In 1830, Algeria was invaded by France; French colonial domination over Algeria eventually supplanted domination by the Ottoman Empire and the Kouloughlis. Western Algeria had already been the hotbed of numerous anti-Ottoman revolts, leading to little in the way of coordinated resistance to the French.

When the French Africa Army reached Oran in January 1831, Abdelkader's father was asked to lead a resistance campaign against them;[1] Muhieddine called for jihad and he and his son were among those involved in early attacks below the walls of the city[6], however these did not involve a broad coalition of tribes[9].

It was at this point that Abdelkader came to the fore. At a meeting of the western tribes in the autumn of 1832, he was elected him Amir al-Mu'minin (typically abbreviated to "Emir") commander of the faithful, and leader of the effort to re-establish order against internal anarchy and foreign incursion. Following his father's refusal of the position on the grounds that he was too old.[10]

Abdelkader was seen as an appropriate candidate not only because of his age but also because of his own learning, devoutness and saintly bloodline[9]. The appointment was confirmed five days later at the Great Mosque of Mascara where a proclamation was read[9] calling in deeply religious terms on tribal leaders to join him.

‘To the communities of the Arabs and Berbers: Know that the affairs of Islamic princely authority and of the upholding of the religious duties of the Muhammadan community have now passed into the hands of the Protector of Religion, the Lord Abdelkeder ibn Muhy al-Din. And the declaration of allegiance has been made to him in recognition thereof, by the ‘ulama, the sharifs, and the notables at Mascara. And he has become our emir and guarantor of the upholding of the bounds of God’s law. He does not follow in the footsteps of any other, nor imitate their example. He does not take a surplus of riches for his own share, as others may have done. He does not burden his subjects in anything save that in which he is commanded by the immaculate shari‘a, and he disposes of nothing save in the proper manner. And he has unfurled the banner of jihad, and bared his forearm to the task, for the welfare of the servants of God, and the prosperity of the land’

— Proclaimation read at Mascara

However he was only one of many claimants to legitimate rule over Algeria, not least the French but also many other tribes from which a multitude made similar claims as he, as well as competition from neighbouring Islamic states (Morocco and the Beys of Tunisia). Indeed the urban elite of Tlemcen expected him to quickly declare vassalage to the sultan of Morocco.

But within a year, through a combination of punitive raids and careful politics, Abdelkader had succeeded in uniting the tribes in the region and in establishing security – his area of influence now covered the entire Province of Oran.[6] The local French commander-in-chief, General Louis Alexis Desmichels, saw Abdelkader as the principal representative of the area during peace negotiations, and in 1834 they signed the Desmichels Treaty, which ceded near-total control of Oran Province to Abdelkader.[1] For the French, this was a way of establishing peace in the region while also confining Abdelkader to the west; but his status as a co-signatory also did much to elevate him in the eyes of the Berbers and of the French.[6]

Even with some security to his position, he still faced great challenges France, Morocco and the Tunisian Beys were stronger states he could only preserve his states independence by balancing rival powers off against each other, through the threat of costly guerrilla warfare and tactical pauses in hostilities[9].

Using this treaty as a start, he imposed his rule on the tribes of the Chelif, Miliana, and Médéa.[1] The French high command, unhappy with what they now saw as the unfavorable terms of the Desmichels Treaty, recalled General Desmichels and replaced him with General Camille Alphonse Trézel, which caused a resumption of hostilities. Abdelkader's tribal warriors met the French forces in July 1834 at the Battle of Macta, where the French suffered an unexpected defeat.[6]

France's response was to step up its military campaign, and under new commanders the French won several important encounters including the 1836 Battle of Sikkak. But political opinion in France was becoming ambivalent towards Algeria, with a political desire to end the conflict General Thomas Robert Bugeaud was "authorized to use all means to induce Abd el-Kader to make overtures of peace".[11] The result, after protracted negotiations, was the Treaty of Tafna, signed on 30 May 1837. This treaty gave even more control of interior portions of Algeria to Abdelkader. Abdelkader thus won control of all of Oran Province and extended his reach to the neighbouring province of Titteri and beyond.[1] What Abdelkader gave up in the treaty is disputed as the Arabic and French texts differ significantly in meaning. Article one of the French treaty reads that Abdelkader ‘recognised the sovereignty of France in Africa’. The Arabic text instead read that "the emir ‘is aware of the rule of French power" (ya‘rifu hukm saltanat firansa) in Africa’.

McDougall argues on the basis of Abdelkader's letters to Bugeaud negotiating the treaty that it cannot have been a translation error and the differing meaning of the texts constitutes duplicity on Bugeaud's part[9].

‘I have understood your power and all the means at your disposal. We do not doubt it and I well know what harm can be done. Power is in the strength of God who created us all and who protects the weakest ... If power lay in numbers, how many times would you have destroyed us?’

— Emir Abdelkader, in a letter to General Bugeaud

In addition to the formal provisions of the Tafna treaty, secret agreements made between Bugeaud and Abdelkader assured the emir that he would obtain army rifles, ammunition, the relocation away from Oran of the secessionist Dawa’ir and Zmala tribes, and the exile of their chiefs in exchange for a cash payment, which was spent by Bugeaud to further his electoral cause through road-mending in his constituency[9]. In this Abdelkader greatly secured his position, enabling the French to fight his Tunisian rivals was no loss. While for a small bribe he had exploited European corruption and internal politics to stabilise his nascent realm, exiling rivals and gaining access to modern weaponry.

New state

[edit]The period of peace following the Treaty of Tafna benefited both sides, and the Emir Abdelkader took the opportunity to consolidate a new functional state, with a capital in Tagdemt. He played down his political power, however, repeatedly declining the title of sultan and striving to concentrate on his spiritual authority.[4] The state he created was broadly theocratic, and most positions of authority were held by members of the religious aristocracy; even the main unit of currency was named the muhammadiyya, after the Prophet.[12]

His first military action was to move south into the Sahara and al-Tijani. Next, he moved east to the valley of the Chelif and Titteri, but was resisted by the Bey of Constantine Province, Hajj Ahmed. In other actions, he demanded punishment of the Kouloughlis of Zouatna for supporting the French. By the end of 1838, his rule extended east to Kabylie, and south to Biskra, and to the Moroccan border.[1] He continued to fight al-Tijani and besieged his capital at Aïn Madhi for six months, eventually destroying it.

Another aspect of Abdelkader that helped him lead his fledgling nation was his ability to find and use good talent regardless of its nationality. He would employ Jews and Christians on his way to building his nation. One of these was Léon Roches.[1] His approach to the military was to have a standing army of 2000 men supported by volunteers from the local tribes. He placed, in the interior towns, arsenals, warehouses, and workshops, where he stored items to be sold for arms purchases from England. Through his frugal living (he lived in a tent), he taught his people the need for austerity and through education he taught them concepts such as nationality and independence.[1]

End of the nation

[edit]The peace ended when the Duc d'Orléans, ignoring the terms of the Treaty of Tafna, headed an expeditionary force that breached the Iron Gates. On 15 October 1839, Abd al-Qadir attacked the French as they were colonizing the Plains of Mitidja and routed the invaders. In response the French officially declared war on 18 November 1839.[13] The fighting bogged down until General Thomas Robert Bugeaud returned to Algeria, this time as governor-general, in February 1841. Abdelkader was originally encouraged to hear that Bugeaud, the promoter of the Treaty of Tafna, was returning; but this time Bugeaud's tactics would be radically different. This time, his approach was one of annihilation, with the conquest of Algeria as the endgame:[1]

I will enter into your mountains, I will burn your villages and your harvests, I will cut down your fruit trees.

— General Bugeaud[13]

Abdelkader was effective at using guerrilla warfare and for a decade, up until 1842, scored many victories. He often signed tactical truces with the French, but these did not last. His power base was in the western part of Algeria, where he was successful in uniting the tribes against the French. He was noted for his chivalry; on one occasion he released his French captives simply because he had insufficient food to feed them. Throughout this period, Abdelkader demonstrated political and military leadership and acted as a capable administrator and a persuasive orator. His fervent faith in the doctrines of Islam was unquestioned.

Until the beginning of 1842 the struggle went in his favor; however, the resistance was put down by Marshal Bugeaud, due to Bugeaud's adaptation to the guerilla tactics employed by Abdelkader. Abdelkader would strike fast and disappear into the terrain with light infantry; however the French increased their mobility. The French armies brutally suppressed the native population and practiced a scorched earth policy in the countryside to force the residents to starve so as to desert their leader. By 1841, his fortifications had all but been destroyed and he was forced to wander the interior of the Oran. In 1842, he had lost control of Tlemcen and his lines of communications with Morocco were not effective. He was able to cross the border into Morocco for a respite, but the French defeated the Moroccans at the Battle of Isly.[1] He left Morocco, and was able to keep up the fight to the French by taking the Sidi Brahim at the Battle of Sidi-Brahim.[1]

Surrender

[edit]

Abdelkader was ultimately forced to surrender. His failure to get support from eastern tribes, apart from the Kabyles of western Kabylie, had contributed to the quelling of the rebellion, and a decree from Abd al-Rahman of Morocco following the 1844 Treaty of Tangiers had outlawed the Emir from his entire kingdom.[12]

Abd al-Rahman of Morocco secretly sent soldiers to attack Abdelkader and destroy his supplies, six months after the emir routed the Moroccans and imprisoned them.[14] Following this failure by the Moroccans, an assassin was sent to kill Emir Abdelkader. While he was reading he raised his head and witnessed a large powerful assassin armed with a dagger, however the assassin quickly threw the dagger to the ground and said: “I was going to strike you, but the sight of you disarmed me. I thought I saw the halo of the Prophet on your head.” [14] The nephew of Abd al-Rahman, Moulay Hashem was sent along with the governor of the Rif, El Hamra in command of a Moroccan army to attack the Emir, however the Moroccans were severely defeated in battle, El Hamra was killed, Moulay Hashem had barely escaped with his life and Abd al-Rahman accepted this defeat.[14][15] The Moroccans led another offensive in the Battle of Agueddin in which they were defeated by Abdelkader in all three military engagements, however Abdelkader soon made the choice to withdraw from Morocco and enter French territory for negotiations.[14]

On 23 December 1847, Abdelkader surrendered to General Louis Juchault de Lamoricière in exchange for the promise that he would be allowed to go to Alexandria or Acre.[1] He supposedly commented on his own surrender with the words, "And God undoes what my hand has done", although this is probably apocryphal. His request was granted, and two days later his surrender was made official to the French Governor-General of Algeria, Henri d'Orléans, Duke of Aumale, to whom Abdelkader symbolically handed his war-horse.[12] Ultimately, however, the French government refused to honour Lamoricière's promise: Abdelkader was shipped to France and, instead of being allowed to carry on to the East, ended up being kept in captivity.[1][12]

Imprisonment and exile

[edit]

Abdelkader and his family and followers were detained in France, first at Fort Lamalgue in Toulon, then at Pau, and in November 1848 they were transferred to the château of Amboise.[1] Damp conditions in the castle led to deteriorating health as well as morale in the Emir and his followers, and his fate became something of a cause célèbre in certain circles. Several high-profile figures, including Émile de Girardin and Victor Hugo, called for greater clarification over the Emir's situation; future prime minister Émile Ollivier carried out a public opinion campaign to raise awareness over his fate. There was also international pressure. Lord Londonderry visited Abdelkader in Amboise and subsequently wrote to then-President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (whom he had known during the latter's exile in England) to appeal for the Emir's release.[12]

Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte (later the Emperor Napoleon III) was a relatively new president, having come to power in the Revolution of 1848 while Abdelkader was already imprisoned. He was keen to make a break with several policies of the previous regime, and Abdelkader's cause was one of them.[12] Eventually, on 16 October 1852, Abdelkader was released by the President and given an annual pension of 100,000 francs[16] on taking an oath never again to disturb Algeria. He then took up residence in Bursa, today's Turkey, moving in 1855 to Amara District in Damascus. He devoted himself anew to theology and philosophy, and composed a philosophical treatise, of which a French translation was published in 1858 under the title of Rappel à l'intelligent, avis à l'indifférent (Reminder to the intelligent, notice to the indifferent), and again in 1877 under the title of Lettre aux Français (Letter to the French). He also wrote a book on the Arabian horse.

During his stay in Syria, 'Abd al-Qadir became an active Freemason and was close to the French intellectual circles.[17][18] He was a prominent member of the lodge of the 'Pyramides', which was directly under the patronage of the Grand Orient of France.[19] While in Damascus, he also befriended Jane Digby as well as Richard and Isabel Burton. Abdelkader's knowledge of Sufism and skill with languages earned Burton's respect and friendship; his wife Isabel described him as follows:

He dresses purely in white…enveloped in the usual snowy burnous…if you see him on horseback without knowing him to be Abd el Kadir, you would single him out…he has the seat of a gentleman and a soldier. His mind is as beautiful as his face; he is every inch a Sultan.[20]

Massacre of Christians in 1860 in Damascus

[edit]In July 1860, conflict between the Druze and Maronites of Mount Lebanon spread to Damascus, and local Druze attacked the Christian quarter, killing over 12,000 people. Abdelkader had previously warned the French consul as well as the Council of Damascus that violence was imminent; when it finally broke out, he sheltered large numbers of Christians, including the heads of several foreign consulates as well as religious groups such as the Sisters of Mercy, in the safety of his house.[13] His eldest sons were sent into the streets to offer any Christians under threat shelter under his protection, and Abdelkader himself was said by many survivors to have played an instrumental part in saving them.

[W]e were in consternation, all of us quite convinced that our last hour had arrived [...]. In that expectation of death, in those indescribable moments of anguish, heaven, however, sent us a savior! Abd el-Kader appeared, surrounded by his Algerians, around forty of them. He was on horseback and without arms: his handsome figure calm and imposing made a strange contrast with the noise and disorder that reigned everywhere.

Reports coming out of Syria as the rioting subsided stressed the prominent role of Abdelkader, and considerable international recognition followed. The French government increased his pension to 150,000 francs and bestowed on him the Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur;[16] he also received the Grand Cross of the Redeemer from Greece, a Star of Magnificence from the Masonic Order of France, the Order of the Medjidie, First Class from Turkey, and the Order of Pope Pius IX from the Vatican.[13] Abraham Lincoln sent him a pair of inlaid pistols (now on display in the Algiers museum) and Great Britain a gold-inlaid shotgun. In France, the episode represented the culmination of a remarkable turnaround, from being considered as an enemy of France during the first half of the 19th century, to becoming a "friend of France" after having intervened in favor of persecuted Christians.[22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29]

In 1865 he visited Paris on the invitation of Napoleon III and was greeted with both official and popular respect. In 1871, during an insurrection in Algeria, he disowned one of his sons, who was arousing the tribes around Constantine.[1]

Death and burial

[edit]Abdelkader died in Damascus on 26 May 1883 and was buried near the great Sufi ibn Arabi in Damascus.

His body was recovered in 1965 and is now in the El Alia Cemetery in Algiers.[30] This transfer of his remains was controversial as Abd el-Kader had clearly wanted to be buried in Damascus with his master, ibn Arabi.

Image and legacy

[edit]-

Abdelkader saving Christians during the Druze/Christian strife of 1860. Painting by Jan-Baptist Huysmans.

-

Two Colt Dragoon revolvers, Lincoln's gift to the Emir

-

Abdelkader in Damascus during 1862

-

Memorial of Emir Abdelkader in Sidi Kada

-

Portrait of Abd el-Kader (1864) by Stanisław Chlebowski

-

The remains of Emir Abdelkader arrived from Syria to Algeria 1965

| Part of a series on |

| Ibn 'Arabi |

|---|

From the beginning of his career, Abdelkader inspired admiration not only from within Algeria, but from Europeans as well,[31][32] even while fighting against the French forces. "The generous concern, the tender sympathy" he showed to his prisoners-of-war was "almost without parallel in the annals of war",[33] and he was careful to show respect for the private religion of any captives.

In 1843 Jean-de-Dieu Soult declared that Abd-el-Kader was one of the three great men then living; the two others, Shamil, 3rd Imam of Dagestan and Muhammad Ali of Egypt also being Muslims.[34]

ʿAbd al-Qādir was involved in research that went into the Bulaq Press's 1911 third edition of Ibn Arabi's Meccan Revelations.[35] This edition was based on the Konya Manuscript, Ibn Arabi's revised version of the text, and it subsequently became standard.[35]

The town of Elkader, Iowa in the United States is named after Abdelkader. The town's founders, Timothy Davis, John Thompson, and Chester Sage, were impressed by his fight against French colonial power and decided to pick his name as the name for their new settlement in 1846.[36]

In 2013, the American film director Oliver Stone announced the pending production of a filmed biopic called The Emir Abd el-Kader, to be directed by Charles Burnett.[37] To date the film has not been made.

The Abd el-Kader Fellowship is a postdoctoral fellowship of The Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia.[38]

On 6 February 2022, a French sculpture of Abdelkader was reported vandalized on 5 February in Amboise, central France. The vandalism occurred amid the presidential election campaign, during which immigration and Islam have been significant issues for specific candidates.[39]

See also

[edit]- Invasion of Algiers in 1830

- Emir Mustapha

- Reghaïa attack (1837)

- Expedition of the Col des Beni Aïcha (1837)

- First Battle of Boudouaou (1837)

- Mokrani Revolt

- French Algeria

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Abdelkader". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-Ak - Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2010. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- ^ Division, American University (Washington, D. C. ) Foreign Areas Studies; Army, United States (1965). U.S. Army Area Handbook for Algeria. U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brower, Benjamin Claude (1 January 2011). "The Amîr ʿAbd Al-Qâdir and the "Good War" in Algeria, 1832-1847". Studia Islamica. 106 (2): 169–195. doi:10.1163/19585705-12341257. ISSN 1958-5705. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ a b Bouyerdene 2012, chapter 3

- ^ Most modern sources give 6 September 1808; but the precise date is not clear. The earliest Arabic sources note his birth as taking place variously between 1221 and 1223 anno hegirae (i.e. AD 1806-1808), with biographical works written by his sons specifying Rajab 1222. For a full discussion of the problem, see Bouyerdene 2012, ch.1 note 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ahmed Bouyerdene, Emir Abd el-Kader: Hero and Saint of Islam, trans. Gustavo Polit, World Wisdom 2012

- ^ Par Société languedocienne de géographie, Université de Montpellier. Institut de géographie, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (France) Publié par Secrétariat de la Société languedocienne de géographie, 1881. Notes sur l'article: v. 4, page 517

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f g McDougall, James (2017). A History of Algeria (1 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-02923-0.

- ^ Ritter, Yusuf. Travels in Algeria, United Empire Loyalists. Tikhanov Library, 2023. "Travels in Algeria, United Empire Loyalists" Archived 2 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Service Historique de l'Armée de Terre, Fonds Serie 1H46, Dossier 2, Province d'Oran, cited in Bouyerdene 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Bouyerdene 2012, chapter 4

- ^ a b c d Bouyerdene 2012, chapter 5

- ^ a b c d The Life of Abdel Kader, Ex-sultan of the Arabs of Algeria: Written from His Own Dictation, and Comp. from Other Authentic Sources. P.253-256. Archived 9 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine Charles Henry Churchill Chapman and Hall, 1867

- ^ Abd-el-Kader, sa vie politique et militaire.P.305 Archived 11 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine Alexandre Bellemare Hachette.

- ^ a b J. Ruedy, Modern Algiera: The Origins and Development of a Nation, (Bloomington, 2005), p. 65; Chateaux of the Loire (Casa Editrice Bonechi, 2007) p10.

- ^ R. RichardsI, Omidvar, Anne, Iraj; K. Al-Rawi, Ahmed (2014). "Chapter 5: Two Muslim Travelers to the West in the Nineteenth Century". Historic Engagements with Occidental Cultures, Religions, Powers. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-137-40502-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Abd-el-Khader. A—Freemason". Library of Congress. 29 March 1862. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Wissa, Karim (1989). "Freemasonry in Egypt 1798-1921: A Study in Cultural and Political Encounters". British Society for Middle Eastern Studies. 16 (2). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 143–161. doi:10.1080/13530198908705494. JSTOR 195148. Archived from the original on 18 December 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2024 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Isabel Burton, Inner Life of Syria, Palestine and the Holy Land, 1875, vol. II, cited in Mary S. Lovell, A Rage to Live: A Biography of Richard and Isabel Burton (1998), Abacus 1999, p. 513

- ^ Cited in Bouyerdene 2012, chapter 5

- ^ "[Les nationalistes] refusent de reconnaitre le rôle d'ami de la France joué par l'émir à Damas sous le Second Empire. En 1860, en effet, Abd-el-Kader intervint pour protéger les chrétiens lors des massacres de Syrie, ce qui lui valut d'être fait grand-croix de la Légion d'honneur par Napoléon III", Jean-Charles Jauffret, La Guerre d'Algérie par les documents, Volume 2, Service historique de l'Armée de terre, 1998, p.174 (ISBN 2863231138)

- ^ "Notre ancien adversaire en Algérie était devenu un loyal ami de la France, et personne n'ignore que son concours nous a été précieux dans les circonstances difficiles" in Archives diplomatiques: recueil mensuel de diplomatie, d'histoire et de droit international, Numéros 3 à 4, Amyot, 1877, p.384

- ^ "Commander of the Faithful: The Life and Times of Emir Abd el-Kader, A Story of True Jihad - Middle East Policy Council". www.mepc.org. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ John W. Kiser, Commander of the Faithful, the Life and Times of Emir Abd El-Kader: A Story of True Jihad, Monkfish Book Publishing Company, 2008

- ^ N. Achrati, Following the Leader: A History and Evolution of the Amir ‘Abd al-Qadir al-Jazairi as Symbol,The Journal of North African Studies Volume 12, Issue 2, 2007 : "The French continued to pay his pension and monitor his activities, and 'Abd al-Qadir remained a self-declared 'friend of France' until his death in 1883."

- ^ Louis Lataillade, Abd el-Kader, adversaire et ami de la France, Pygmalion, 1984, ISBN 2857041705

- ^ Priestley, Herbert Ingram (1938). France Overseas: A Study Of Modern Imperialism, 1938. Octagon Books. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7146-1024-5.

[Abdelkader was] transferred to Damascus by Napoleon III. There he became a friend of France, saving twelve thousand Christians from the Turks at the time of the massacres in Damascus, and refused to ally himself with the insurgents in Algeria in 1870.

- ^ Morris, Robert (2015). Freemasonry in the Holy Land: or, Handmarks of Hiram's Builders. Westphalia Press. p. 577. ISBN 978-1633912205.

- ^ Moubayed, Sami (19 October 2023). The Damascus Seat of Power: Syria's Heads of State, 1918-1946. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-7556-4921-1.

- ^ Dinesen

- ^ Bouyerdene, p45-47 "scrupulous respect for the law, the foundation of which is humanity and justice"

- ^ Charles Henry Churchill, Life of Abd el-Kader: Ex-Sultan of the Arabs of Algeria, 1887

- ^ Alexandre Bellemare, Abd-el-Kader sa vie politique et militaire, Hachette, 1863, p.4

- ^ a b "al-Futuhat al-Makiyya Printed Editions". Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi Society. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ "History of Elkader, IA". Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ Sneider, Jeff (8 October 2013). "Oliver Stone to Executive Produce Biopic of Algerian Leader Emir Abd el-Kader". TheWrap. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ "Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture". Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ "Emir Abdelkader: French sculpture of Algerian hero vandalised". BBC News. 6 February 2022. p. 1. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

Bibliography and further reading

[edit]- Ritter, Yusuf. Travels in Algeria, United Empire Loyalists. Tikhanov Library, 2023. "Travels in Algeria, United Empire Loyalists"

- Bouyerdene, Ahmed Emir Abd el-Kader: Hero and Saint of Islam, trans. Gustavo Polit, World Wisdom 2012, ISBN 978-1936597178

- Churchill, Charles Henry Life of Abd el-Kader: Ex-Sultan of the Arabs of Algeria: written and compiled from his own dictation from other Authentic Sources, Nabu Press 2014, ISBN 978-1294672289, Reprint from Chapman and Hall 1867

- Danziger, Raphael. Abd al-Qadir and the Algerians: Resistance to the French and Internal Consolidation. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1977.

- Dinesen, A. W. Abd el-Kader, 1840 (reprint 2006), ISBN 8776950301

- Dupuch, Antoine-Adolphe (1849). Abd-el-Kader au château d'Amboise. Bordeaux: Imprimerie de H. Faye. OCLC 457413515.

- Dupuch, Antoine-Adolphe (1860). Abd-el Kader : Sa vie intime, sa lutte avec la France, son avenir. Bordeaux: Lacaze. OCLC 493227699.

- Étienne, Bruno. Abdelkader. Paris: Hachette Littérature, 2003.

- Kiser, John W. Commander of the Faithful: The Life and Times of Emir Abd El-Kader, Archetype 2008, ISBN 978-1901383317

- Marston, Elsa. The Compassionate Warrior: Abd El-Kader of Algeria, Wisdom Tales 2013, ISBN 978-1937786106

- Pitts, Jennifer, trans. and ed. Writings on Empire and Slavery by Alexis de Tocqueville. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- Woerner-Powell, Tom. Another Road to Damascus: An integrative approach to ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jazā'irī (1808–1883), De Gruyter 2017, ISBN 978-3-11-049699-4

External links

[edit]- "Alexis de Tocqueville's First Letter on Algeria". Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- Abd Al-Kadir's Struggle for Truth

- Science sacrée, Revue d'études traditionnelles

- When Americans Honored an Icon of Jihad - John Kiser's video on Emir Abdelkader al-Jazairi

- Famous Quotes by Abd al-Qadir

- Emir Abdelkader collected news and commentary at The New York Times

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I (9th ed.). 1878. p. 30.

- "Abd-el-Kadir". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

- "Abd-el-Kader". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I (11th ed.). 1911. p. 32.

- "Abd-el-Kader". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Abd-el-Kader". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- 1808 births

- 1883 deaths

- 19th-century Algerian people

- Algerian guerrillas

- Algerian resistance leaders

- Algerian Sufis

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

- Hashemite people

- Heads of state in Africa

- History of Damascus

- Algerian independence activists

- People from Mascara Province

- Supporters of Ibn Arabi

- Religious leaders in Africa

- Emirate of Abdelkader