Palestinian Christians

The Palestinian flag | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~500,000 (~6.5% of the global Palestinian population) (1990s–2000s estimate) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| |

| Languages | |

| Palestinian Arabic |

| Part of a series on |

| Palestinians |

|---|

|

| Demographics |

| Politics |

|

| Religion / religious sites |

| Culture |

| List of Palestinians |

Palestinian Christians (Arabic: مَسِيحِيُّون فِلَسْطِينِيُّون Masīḥiyyūn Filasṭīniyyūn) are a religious community of the Palestinian people consisting of those who identify as Christians, including those who are cultural Christians in addition to those who actively adhere to Christianity. They are a religious minority within the State of Palestine and within Israel, as well as within the Palestinian diaspora. Applying the broader definition, which groups together individuals with full or partial Palestinian Christian ancestry, the term was applied to an estimated 500,000 people globally in the year 2000.[1] As most Palestinians are Arabs, the overwhelming majority of Palestinian Christians also identify as Arab Christians.

Palestinian Christians belong to one of a number of Christian denominations, including Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, Catholicism (both the Latin Church and the Eastern-Rite Churches), and Protestantism (Anglicanism, Lutheranism, etc.), among others. In the 1990s, an estimate by Professor Bernard Sabella of Bethlehem University postulated that approximately 6.5% of the global Palestinian population was Christian, and that 56% of this figure was living outside of Palestine and Israel.[2]

As of 2015[update], Palestinian Christians comprise between 1% and 2.5% of the population of the West Bank, and about 3,000 (0.13%) of the population of the Gaza Strip.[3][4] According to official British Mandate statistics, Christians accounted for 9.5% of the total population (and 10.8% of Palestine's Arabs) in 1922 and 7.9% of the total population in 1946.[5] Over the course of the 1947–1949 Palestine war between the Palestinian Arabs and the Palestinian Jews, a large number of these Christians—as part of the Arab community—fled or were expelled by Jewish militias from what would become recognized as Israeli territory following the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Since the 1967 Arab–Israeli War, which resulted in Israel's occupation of the Palestinian territories (the Jordanian-annexed West Bank and the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip), the Palestinian Christian population has increased as a whole, but has decreased as a percentage of the total Palestinian population.[6]

Many individuals of the Palestinian diaspora who identify as Christians are descendants of the post-1948 Palestinian Christian refugees who fled from the Arab–Israeli conflict and settled in Christian-majority countries.[7][8]

Ethnic identity

Most Palestinian Christians nowadays see themselves as culturally and linguistically Arab Christians with ancestors dating back to the first followers of Christ. They claim descent from Romans, Ghassanid Arabs, Byzantines, and Crusaders.[9]

That Christian Arabs in Palestine see themselves as Arab nationalistically reflects also the fact that, as of the beginning of the twentieth century, they shared many of the same customs as their Muslim neighbors. In some respects, this was a consequence of Christians adopting what were essentially Islamic practices, many of which were derived of sharî'ah. In others, it was more the case that the customs shared by both Muslims and Christians derived from neither faith, but rather were a result of a process of syncretization, whereby what had once been pagan practices were later redefined as Christian and subsequently adopted by Muslims. This was especially evident in the fact that Palestine's Muslims and Christians shared many of the same feast days, in honor of the same saints, even if they referred to them by different names. "Shrines dedicated to St. George, for instance, were transformed into shrines honoring Khidr-Ilyas, a conflation of the Prophet Elijah and the mythical sprite Khidr". Added to this, many Muslims viewed local Christian churches as saints' shrines. Thus, for instance, a "Muslim women having difficulties conceiving, for instance, might travel to Bethlehem to pray for a child before the Virgin Mary".[10] It was even not uncommon for a Muslim to have his child baptized in a Christian church, in the name of Khaḍr.[11]

Geographic distribution

In 2009, there were an estimated 50,000 Christians in the Palestinian territories, mostly in the West Bank, with about 3,000 in the Gaza Strip.[12] In 2022, about 1,100 Christians lived in the Gaza Strip – down from over 1300 in 2014.[13] About 80% of the Christian Palestinians live in an urban environment. In the West Bank, they are concentrated mostly in Jerusalem and its vicinity: Bethlehem, Beit Jala, Beit Sahour, Ramallah, Bir Zayt, Jifna, Ein Arik, Taybeh.[14]

Of the total Christian population of 185,000 in Israel, about 80% are designated as Arabs, many of whom self-identify as Palestinian.[15][12][16]

The majority (56%) of Palestinian Christians live in the Palestinian diaspora.[17]

Demographics and denominations

1922 census

In the 1922 census of Palestine there were approximately 73,000 Christian Palestinians: 46% Orthodox, 40% Catholic (20% Roman Catholic, and 20% Eastern Catholic).

The census recorded over 200 localities with a Christian population.[18] The totals by denomination for all of Mandatory Palestine were: Greek Orthodox 33,369, Syriac Orthodox (Jacobite) 813, Latin Catholic 14,245, Greek Catholic (Melkite) 11,191, Syriac Catholic 323, Armenian Catholic 271, Maronite 2,382, Armenian Orthodox (Gregorian) 2,939, Coptic Church 297, Abyssinian Church 85, Church of England 4,553, Presbyterian Church 361, Protestants 826, Lutheran Church 437, Templars Community 724, others 208.[18]

The census also listed 10,707 Palestinian Christians living abroad, making up the largest portion of the Palestinians living abroad at the time: 32 in Australia, 17 in Africa, 1 in Austria, 1 in Belgium, 1 in Bulgaria, 2 in Canada, 242 in Egypt, 34 in France, 59 in Germany, 1 in Greece, 7 in Italy, 4 in Morocco, 1 in Mesopotamia, 1 in Paraguay, 5 in Persia, 4 in Russia, 1 in South Africa, 11 in East Africa, 7 in Sudan, 6 in Sweden, 1 in Switzerland, 2 in Spain, 122 in Syria, 95 in Transjordan, 8,517 in South and Central American republics, 17 in Turkey, 6 in the United Kingdom, 1,352 in the United States, and 158 whose locations were unknown.[19]

Denominations and Church Leadership

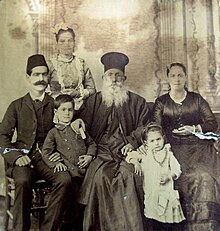

Around 50% of Palestinian Christians belong to the Greek Orthodox Church of Jerusalem[citation needed], one of the 15 churches of Eastern Orthodoxy. This community has also been known as the Arab Orthodox Christians. There are also Maronites, Melkites, Jacobites, Chaldeans, Latin Catholics, Syriac Catholics, Orthodox Copts, Coptic Catholics, Armenian Orthodox, Armenian Catholics, Quakers (Society of Friends), Methodists, Presbyterians, Anglicans (Episcopal), Lutherans, Evangelicals, Pentecostals, Nazarene, Assemblies of God, Baptists and other Protestants; in addition to small groups of Jehovah's Witnesses, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and others.

Patriarch Theophilos III is the leader of the Greek Orthodox Church of Jerusalem since 2005. He replaced Irenaios (in office from 2001), who was deposed by the church synod after a term surrounded by controversy and scandal over a sale of property owned by the Greek Orthodox Church to Jewish investors.[20] The Israel government initially refused to recognize Theophilos's appointment[21] but finally granted full recognition in December 2007, despite a legal challenge by his predecessor Irenaios.[22] Archbishop Theodosios (Hanna) of Sebastia [when?] the highest ranking Palestinian clergyman in the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem.

The Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem is the leader of the Latin Catholics in Jerusalem, Palestine, Jordan, Israel and Cyprus. The office has been held by Pierbattista Pizzaballa since his appointment by Pope Francis on 6 November 2020.[23] George Bacouni, of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, is Archbishop of Akka, with jurisdiction over Haifa, Acre and the Galilee, and replaced Elias Chacour, a Palestinian refugee, in 2014. Moussa El-Hage, of the Maronite Church, is since 2012 simultaneously Archbishop of the Archeparchy of Haifa and the Holy Land and Patriarchal Exarch of Jerusalem and Palestine.

The Anglican Bishop in Jerusalem is Suheil Dawani,[24] who replaced Bishop Riah Abou Al Assal. Bishop Dr. Munib Younan is the president of the Lutheran World Federation and the Bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Jordan and the Holy Land (ELCJHL).

List of Churches in Palestine

International Christian Organisations in Palestine

Various international Christian organisations provide services in Palestine to Palestinians of all religious backgrounds.

- YMCA in Gaza and Jerusalem

- The Anglican Church runs the Al-Ahli Arab Hospital

Christian development assistance

A study showed $416 million annual spending of Christian institutions on Palestinian society, in sectors such as health care, education, social services, vocational training and development assistance interventions in all Palestinian governorates.[25]

History

Background and early history

The first Christian communities in Roman Judea originated from the followers of Jesus of Nazareth, who was put to death and crucified by order of Prefect Pontius Pilate in 30–33; they were Aramaic speaking Jewish Christian and, later, Latin and Greek-speaking Romans and Greeks, who were in part descendants from previous settlers of the regions, such as Syro-Phoenicians, Arameans, Greeks, Persians, and Arabs such as Nabataeans.[28][verification needed]

Contrary to other groups of oriental Christians such as the largely Assyrian Nestorians, the vast majority of Palestinian Christians went under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and Roman emperors after the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD (which would be part of the Eastern Orthodox Church after the Great Schism), and were known by other Syrian Christians as Melkites (followers of the king).[29] The Melkites were heavily Hellenised in the following centuries, abandoning their distinct Western Aramaic languages in favour of Greek. By the 7th century, Jerusalem, Gaza and Byzantine Palestine became the epicentre of Greek culture in the Orient.[29]

In the fourth century, the monk Hilarion introduced monasticism in the area around Gaza which became a flourishing monastic center (including the Saint Hilarion Monastery and the monastery of Seridus), second only to the cluster of monasteries in the Judaean desert (which include the Mar Saba monastery).[30]

Following Muslim conquests, non-Arabic speaking Christians underwent a gradual process of Arabization in which they abandoned Aramaic and Greek in favor of Arabic.[31][29] The Melkites began abandoning Greek for Arabic, a process which made them the most Arabicised Christians in the Levant.[29] Most Arab Ghassanids remained Christian and joined Melkite and Syriac communities within what is now Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon.[32]

The eleventh century Melkite bishop of Gaza Sulayman al-Ghazzi holds a unique place in the history of Arab Christian literature as author of the first diwan of Christian religious poetry in Arabic. His poems give insights into the life of Palestinian Christians and the persecution they suffered under Fatimid caliph al-Hakim.[33]

In the late sixteenth century, Christianity in southern Bilad ash-Sham was primarily rural, with a significant portion of the population living in villages and tribes. Christians were dispersed among numerous towns and villages in the vicinity of Jerusalem, some had been inhabited by Christians since Byzantine and Frankish rule. Villages with Christian population included Taybeh, Beit Rima, Jifna an-Nasara, Ramallah, Yabrud, Aboud, Suba, Tuqu, Nahalin, and Artas. The Christians living in these villages were mainly of Greek Orthodox denomination, although exceptions existed, such as the Syrian Christian community in Aboud.[34]

Modern history

During the Ottoman Empire, foreign powers enjoyed positions of guardianship towards minorities, including the French for the Christians of Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. Orthodox Christians more specifically came under the protections of the Russian Empire. This placed Palestinian Christians with protection privileges, and access to missionary schools, which enabled them to engage in commerce with European traders. In addition, Christian merchants had lower rates of duty to pay than their Muslim counterparts, and thus they established themselves as bankers and moneylenders for Muslim landowners, artisans and peasants. This growing middle class produced several newspaper owners and editors and played leading roles in Palestinian political life.[35]

The category of 'Palestinian Arab Christian' came to assume a political dimension in the 19th century as international interest grew and foreign institutions were developed there. The urban elite began to undertake the construction of a modern multi-religious Arab civil society. When the British received from the League of Nations a mandate to administer Palestine after World War I, many British dignitaries in London were surprised to discover so many Christian leaders in the Palestinian Arab political movements. The British authorities in the Mandate of Palestine had difficulty understanding the commitment of the Palestinian Christians to Palestinian nationalism.[36]

Palestinian Christian-owned Falastin was founded in 1911 in the then Arab-majority city of Jaffa. The newspaper is often described as one of the most influential newspapers in historic Palestine, and probably the nation's fiercest and most consistent critic of the Zionist movement. It helped shape Palestinian identity and nationalism and was shut down several times by the Ottoman and British authorities, most of the time due to complaints made by Zionists.[37] Following the British takeover of Palestine in 1918 during the final stages of the First World War, groups called "Muslim-Christian Associations" were formed across the new Mandatory Palestine in order to oppose the Zionist movement and implementation of the Balfour Declaration.[38] In the 1920s, it was noted that the inhabitants of Beit Kahil, Dayr Aban and Taffuh were originally Christian.[39]

The Nakba left the multi-denominational Christian Arab communities in disarray. They had little background in theology, their work being predominantly pastoral, and their immediate task was to assist the thousands of homeless refugees. But it also sowed the seeds for the development of a Liberation Theology among Palestinian Arab Christians.[40] There was a differential policy of expulsion. More lenience was applied to the Christians of the Galilee where expulsion mostly affected Muslims: at Tarshiha, Me'eliya, Dayr al-Qassi, and Salaban, Christians were allowed to remain while Muslims were driven out.[citation needed] At Iqrit and Bir'im the IDF ordered Christians to evacuate for a brief spell, an order that was then confirmed as a permanent expulsion. Sometimes in a mixed Druze-Christian village like al-Rama, only the Christians were initially expelled towards Lebanon, but, thanks to the intervention of the local Druze, they were permitted to return. Important Christian figures were sometimes allowed to return, on condition they help Israel among their communities. Archbishop Hakim, with many hundreds of Christians, was allowed reentry on expressing a willingness to campaign against Communists in Israel and among his flock.[41]

After the war of 1948, the Christian population in the West Bank, under Jordanian control, dropped slightly, largely due to economic problems. This contrasts with the process occurring in Israel where Christians left en masse after 1948. Constituting 21% of Israel's Arab population in 1950, they now make up just 9% of that group. These trends accelerated after the 1967 war in the aftermath of Israel's takeover of the West Bank and Gaza.[42]

In the Palestinian Authority (from 1994)

Christians within the Palestinian Authority constituted around one in seventy-five residents.[43] In 2009, Reuters reported that 47,000–50,000 Christians remained in the West Bank, with around 17,000 following the various Catholic traditions and most of the rest following the Orthodox church and other eastern denominations.[12] Both Bethlehem and Nazareth, which were once overwhelmingly Christian, now have Muslim majorities. Today about three-quarters of all Bethlehem Christians live abroad, and more Jerusalem Christians live in Sydney, Australia, than in Jerusalem. Christians now comprise 2.5 percent of the population of Jerusalem. Those remaining include a few born in the Old City when Christians there constituted a majority.[44]

In a 2007 letter from Congressman Henry Hyde to President George W. Bush, Hyde stated that "the Christian community is being crushed in the mill of the bitter Israeli-Palestinian conflict" and that expanding Jewish settlements in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, were "irreversibly damaging the dwindling Christian community".[45][46]

In November 2009, Berlanty Azzam, a Palestinian Christian student from Gaza, was expelled from Bethlehem and was not allowed to continue her studying. She had two months left for the completion of her degree. Berlanty Azzam said the Israeli military handcuffed her, blindfolded her, and left her waiting for hours at a checkpoint on her way back from a job interview in Ramallah. She described the incident as "frightening" and claimed Israeli official treated her like a criminal and denied her an education because she is a Palestinian Christian from Gaza.[47]

In Israel

In July 2014, during operation Protective Edge an Israeli-Arab Christian demonstration was held in Haifa in a protest against Muslim extremism in the Middle East (concerning the rise of the Islamic State) and in support of Israel and the IDF.[48]

Christian Arabs are one of the most educated groups in Israel.[49][50] Statistically, Christian Arabs in Israel have the highest rates of educational attainment among all religious communities, according to a data by Israel Central Bureau of Statistics in 2010, 63% of Israeli Christian Arabs have had college or postgraduate education, the highest of any religious and ethno-religious group.[51] Despite the fact that Arab Christians only represent 2.1% of the total Israeli population, in 2014 they accounted for 17.0% of the country's university students, and for 14.4% of its college students.[52] Christians are proportionally more likely to have attained a bachelor's or higher academic degrees than the Israeli national average. Christian Arabs additionally have one of the highest rates of success in the matriculation examinations, (73.9%) in 2017[53][54] both in comparison to the Muslims and the Druze and in comparison to all students in the Jewish education system as a group.[55] Arab Christians were also the vanguard in terms of eligibility for higher education,[55] and they have attained a bachelor's degree and academic degree more than the median Israeli population.[55] Christians schools in Israel went on strike in 2015 at the beginning of the 2015 academic year in protest at budget cuts aimed at them. The strike affected 33,000 pupils, 40 percent of them Muslim. In 2013, Israel covered 65% of the budget of Palestinian Christian schools in Israel, a figure cut that year to 34%. Christians say they now received a third of what Jewish schools receive, with a shortfall of $53 million.[56]

The rate of students studying in the field of medicine was also higher among the Christian Arab students, compared with all the students from other sectors. The percentage of Arab Christian women who are higher education students is higher than other sectors.[57]

In September 2014, Israel's interior minister signed an order that the self-identified ''Aramean Christian'' minority in Israel could register as Arameans rather than Arabs.[58] The order will affect about 200 families.[58]

The first local woman cleric ordained in the Holy Land was Palestinian Sally Azar of the Lutheran church in 2023.[59]

Israel-Hamas War

Since the start of the ongoing Israel–Hamas war in October 2023, there have been several incidents involving Palestinian Christians in the Gaza Strip, most notably the Church of Saint Porphyrius airstrike and the killing of two Catholic women by an Israeli sniper in the Holy Family Parish in northern Gaza.[60][61]

Political and ecumenical issues

The mayors of Ramallah, Birzeit, Bethlehem, Zababdeh, Jifna, Ein 'Arik, Aboud, Taybeh, Beit Jala and Beit Sahour are Christians. The Governor of Tubas, Marwan Tubassi, is a Christian. The former Palestinian representative to the United States, Afif Saffieh, is a Christian, as is the ambassador of the Palestinian Authority in France, Hind Khoury. The Palestinian women's football team has a majority of Muslim girls, but the captain, Honey Thaljieh, is a Christian from Bethlehem. Many of the Palestinian officials such as ministers, advisers, ambassadors, consulates, heads of missions, PLC, PNA, PLO, Fateh leaders and others are Christians. Some Christians were part of the affluent segments of Palestinian society that left the country during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. In West Jerusalem, over 50% of Christian Palestinians lost their homes to the Israelis, according to the historian Sami Hadawi.[62]

Involvement in Palestinian militancy

Palestinian Christians have played a role in the anti-Zionist movement and related political violence, both before and after the establishment of Israel in 1948.

Four out of the 282 Palestinian Arab rebel leaders that participated in the 1936-1939 revolt in British Palestine were Christians. The rebels bore flags with a cross and crescent, symbolizing Christianity and Islam, respectively.[63]

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) was founded in 1967 by George Habash, a Christian.[64][65][66] Habash once stated that he believed there was perfect harmony between his Christian religion, his Arab nationalism, his Islamic culture, and his Marxist politics.[67] Wadie Haddad, the leader of the military wing of the PFLP, was also Christian.[68][69] Reportedly, Eastern Orthodox priests would bless PFLP hijacking teams before they set out on attacks.[70]

Sirhan Sirhan, who assassinated Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, came from a Christian family[71][72] and later changed church denominations several times, joining Baptist and Seventh-day Adventist churches.[73] However, in 1966, he joined the esoteric organization Ancient Mystical Order of the Rose Cross, one of the Rosicrucian Orders.[74]

Luttif Afif, the commander of the Black September Organization (BSO) unit that carried out the 1972 Munich massacre, was reported to have at least a partial Christian background.[75][76][77] He used the alias "Jesus",[78] and named the Munich operation "Iqrit and Biram",[79][80][81] after two Christian villages whose inhabitants were expelled by the IDF during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[82][83][84] Theresa Halaseh, another member of the BSO, was a Christian[85][86][87] and also a Fatah member.[88] She participated in the BSO hijacking of Sabena Flight 571, and was captured but later released in a 1983 prisoner exchange.[89][90]

There have been at least two known Christian militants from the Al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades, Chris Bandak and Daniel Saba George, both from Bethlehem. Bandak was imprisoned by Israel for shooting at Israeli motorists during the Second Intifada,[91][92] and at that time was described as the only Christian in the entire Al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades.[93][94][95] However, during a meeting with Bandak's family in 2009, Palestinian Authority official Issa Qaraqe hinted that there were other imprisoned Christian militants as well.[91] Bandak was later released in 2011 as part of an exchange for the release of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit.[96] Daniel Saba George ("Abu Hamama"), who was also a senior Tanzim operative, was killed by Israel in 2006.[97] An image was later taken of George's Christian funeral in Bethlehem,[98] and a poster of him with Christian imagery was seen put up in the city that same year.[99]

Arab Orthodox Movement

The Arab Orthodox Movement is a political and social movement aiming for the Arabization of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem, the church overseeing Orthodox communities in Palestine, Israel and Jordan; to which the majority of the Christian population there belongs to.[100]

Within the context of rising Arab nationalism in the 19th century, the movement was inspired by the successful precedent of the Arabization of Syria and Lebanon's Antioch Patriarchate in 1899. The movement seeks the appointment of an Arab patriarch, Arab laity control over Jerusalem patriarchate's properties for social and educational purposes, and the use of Arabic as a liturgical language.[101] Initially a church movement among Palestine and Transjordan's Orthodox Arab Christians in the late 19th century, it was later supported as a Palestinian and Arab nationalist cause and championed by some Arab Muslims, owing to the Greek-dominated patriarchate's early support to Zionism.[101]

The Orthodox laity, which is mostly Arab, maintains that the patriarchate was forcibly Hellenized in 1543, while the Greek clergy says that the patriarchate was historically Greek.[101] Opposition to the Greek clergy turned violent in the late 19th century, when they came under physical attack by the Arab laity in the streets. The movement was subsequently focused on holding Arab Orthodox conferences, the first of which was held in Jaffa in 1923, and most recently in Amman in 2014. One outcome of the 1923 conference was the laity's establishment of tens of Orthodox churches, clubs and schools in Palestine and Jordan over the decades.[102] There were historically also several interventions to solve the conflict by the Ottoman, British (1920–1948), and Jordanian (1948–1967) authorities, owing to the patriarchate's headquarters being located in East Jerusalem.[103]

Christian converts from Islam

Though numbering only a few hundred, there is a community of Christians who have converted from Islam. They are not centered in one particular city and mostly belong to various evangelical and charismatic communities. Due to the fact that official conversion from Islam to Christianity is illegal in accordance with Islamic sharia law in Palestine, these individuals tend to keep a low profile.[104]

Ecumenical Liberation Theology Center: Sabeel

The Sabeel Ecumenical Liberation Theology Center is a Christian non-governmental organization based in Jerusalem; was founded in 1990 as an outgrowth of a conference regarding "Palestinian Liberation Theology."[105] According to its web site, "Sabeel is an ecumenical grassroots liberation theology movement among Palestinian Christians. Inspired by the life and teaching of Jesus Christ, this liberation theology seeks to deepen the faith of Palestinian Christians, to promote unity among them toward social action. Sabeel strives to develop a spirituality based on love, justice, peace, nonviolence, liberation and reconciliation for the different national and faith communities. The word "Sabeel" is Arabic for 'the way' and also a 'channel' or 'spring' of life-giving water."[106]

Sabeel has been criticized for its belief that "Israel is solely culpable for the origin and continuation of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict,"[107] and for using "anti-Semitic deicide imagery against Israel, and of disparaging Judaism as 'tribal,' 'primitive,' and 'exclusionary,' in contrast to Christianity’s 'universalism' and 'inclusiveness.'"[107][108] In addition, Daniel Fink, writing on behalf of NGO Monitor, shows that Sabeel leader Naim Ateek has described Zionism as a "step backward in the development of Judaism", and Zionists as "oppressors and war makers".[109][110][111]

"Kairos Palestine" document (2009)

In December 2009, a number of prominent Palestinian Christian activists, both clergy and lay people,[112] released the Kairos Palestine document, "A moment of truth." Among the authors of the document are Michel Sabbah, former Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, Archbishop Attalah Hanna, Father Jamal Khader, Rev. Mitri Raheb, Rev. Naim Ateek and Rifat Kassis who is the coordinator and chief spokesperson of the group.

The document declares the Israeli occupation of Palestine a "sin against God" and against humanity. It calls on churches and Christians all over the world to consider it and adopt it and to call for the boycott of Israel. Section 7 calls for "the beginning of a system of economic sanctions and boycott to be applied against Israel." It states that isolation of Israel will cause pressure on Israel to abolish all of what it labels as "apartheid laws" that discriminate against Palestinians and non-Jews.[113]

Holy Land Christian Ecumenical Foundation

The Holy Land Christian Ecumenical Foundation (HCEF) was founded in 1999 by an ecumenical group of American Christians to preserve the Christian presence in the Holy Land. HCEF stated goal is to attempt to continue the presence and well-being of Arab Christians in the Holy Land and to develop the bonds of solidarity between them and Christians elsewhere. HCEF offers material assistance to Palestinian Christians and to churches in the area. HCEF advocates for solidarity on the part of Western Christians with Christians in the Holy Land.[114][115][116]

Christians of Gaza

In 2022, there were approximately 1,100 Christians in the Gaza Strip, down from 1,300 in 2013, [13] and from 5,000 in the mid-1990s.[117] Gaza's Christian community mostly lives within the city, especially in areas neighbouring the three main churches: Church of Saint Porphyrius, The Holy Family Catholic Parish in Zeitoun Street, and the Gaza Baptist Church, in addition to an Anglican chapel in the Al-Ahli Al-Arabi Arab Evangelical Hospital. Saint Porphyrius is an Orthodox Church that dates back to the 12th century. Gaza Baptist Church is the city's only Evangelical Church; it lies close to the Legislative Council (parliamentary building). While some reports claim that Christians in Gaza freely practice their religion and may observe all the religious holidays in accordance with the Christian calendars followed by their churches.[118] other reports claim forceful conversion to Islam, public insults, kidnapping, fear of radical Islamist groups,[119] and vandalism.[117]

Those among them working as civil servants in the government and in the private sector are given an official holiday during the week, which some devote to communal prayer in churches. Christians are permitted to obtain any job, in addition to having their full rights and duties as their Muslim counterparts in accordance with the Palestinian Declaration of Independence, the regime, and all the systems prevailing over the territories. Moreover, seats have been allocated to Christian citizens in the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) in accordance with a quota system that allocates based on a significant Christian presence.

A census revealed that 40 percent of the Christian community worked in the medical, educational, engineering and law sectors. Additionally, the churches in Gaza are renowned for the relief and educational services that they offer, and Muslim citizens participate in these services. Palestinian citizens as a whole benefit from these services. The Latin Patriarchate School, for example, offers relief in the form of medication and social and educational services. The school has been offering services for nearly 150 years.

In 1974, the idea of establishing a new school was proposed by Father Jalil Awad, a former parish priest in Gaza who recognized the need to expand the Latin Patriarchate School and build a new complex. In 2011, the Holy family school had 1,250 students and the Roman Catholic primary school, which is an extension of the Latin Patriarchate School, continues to enroll a rising number of young students. The primary school was established approximately 20 years ago. Aside from education, other services are offered to Muslims and Christians alike with no discrimination. Services include women's groups, students' groups and youth groups, such as those offered at the Baptist Church on weekdays.[citation needed] As of 2013, only 113 out of 968 of these Christian schools’ students were in fact Christians.[120]

In October 2007, Rami Ayyad, the Baptist manager of The Teacher's Bookshop, the only Christian bookstore in the Gaza Strip, was murdered, following the firebombing of his bookstore and the receipt of death threats from Muslim extremists.[121][122]

In 2008, the gate of the Rosary Sisters School was blown up, and the library of a Christian organization for youth was blown up with the guard being kidnapped.[117]

From the 3,000 Christians in 2007 when Israel intensified its siege and drove them out of the poor area, estimates indicate that the number of Christians in Gaza has decreased since. With a history stretching back to the first century, the 800–1,000 Christians who are thought to still be in Gaza represent the oldest Christian community in the world. At least eighteen people were killed when Israel bombed the Church of Saint Porphyrius, which is the oldest in Gaza, on 19 October 2023.[123]

Christian emigration

In addition to neighboring countries, such as Lebanon and Jordan, many Palestinian Christians emigrated to countries in Latin America (notably Argentina and Chile), as well as to Australia, the United States and Canada. The Palestinian Authority is unable to keep exact tallies.[12] The share of Christians in the population has also decreased due to the fact that Muslim Palestinians generally have much higher birth rates than the Christians.[20][124]

The causes of this Christian exodus are hotly debated, with various possibilities put forth.[43] Many of the Palestinian Christians in the diaspora are those who fled or were expelled during the 1948 war and their descendants.[17] After discussion between Yosef Weitz and Moshe Sharett, Ben-Gurion authorized a project for the transference of the Christian communities of the Galilee to Argentina, but the proposal failed in the face of Christian opposition.[125][126][127] Reuters has reported that the emigrants since then have left in pursuit of better living standards.[12]

The BBC has also blamed the economic decline in the Palestinian Authority as well as pressure from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for the exodus.[124] A report on Bethlehem residents stated both Christians and Muslims wished to leave but the Christians possessed better contacts with people abroad and higher levels of education.[128] The Vatican and the Catholic Church blamed the Israeli occupation and the conflict in the Holy Land for the Christian exodus from the Holy Land and the Middle East in general.[129]

The Jerusalem Post (an Israeli newspaper) has stated that the "shrinking of the Palestinian Christian community in the Holy Land came as a direct result of its middle-class standards" and that Muslim pressure has not played a major role according to Christian residents themselves. It reported that the Christians have a public image of elitism and of class privilege as well as of non-violence and of open personalities, which leaves them more vulnerable to criminals than Muslims. Hanna Siniora, a prominent Christian Palestinian human rights activist, has attributed harassment against Christians to "little groups" of "hoodlums" rather than to the Hamas and Fatah governments.[43] In his last novel, the Palestinian Christian writer Emile Habibi has a character affirm that: "There is no difference between Christian and Muslim: we are all Palestinian in our predicament."[130]

According to a report in The Independent, thousands of Christian Palestinians "emigrated to Latin America in the 1920s, when Mandatory Palestine was hit by drought and a severe economic depression."[131]

Today, Chile houses the largest Palestinian Christian community in the world outside of the Levant. As many as 350,000 Palestinian Christians reside in Chile, most of whom came from Beit Jala, Bethlehem, and Beit Sahur.[132] Also, El Salvador, Honduras, Brazil, Colombia, Argentina, Venezuela, and other Latin American countries have significant Palestinian Christian communities, some of whom immigrated almost a century ago during the time of Ottoman Palestine.[133]

In a 2006 poll of Christians in Bethlehem by the Palestinian Centre for Research and Cultural Dialogue, 90% reported having Muslim friends, 73% agreed that the Palestinian Authority treats Christian heritage in the city with respect, and 78% attributed the ongoing exodus of Christians from Bethlehem to the Israeli occupation and travel restrictions on the area.[134] Daniel Rossing, the Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs' chief liaison to Christians in the 1970s and 1980s, has stated that the situations for them in Gaza became much worse after the election of Hamas. He also stated that the Palestinian Authority, which counts on Christian westerners for financial support, treats the minority fairly. He blamed the Israeli West Bank barrier as the primary problem for the Christians.[43]

The United States State Department's 2006 report on religious freedom criticized both Israel for its restrictions on travel to Christian holy sites and the Palestinian Authority for its failure to stamp out anti-Christian crime. It also reported that the former gives preferential treatment in basic civic services to Jews and the latter does so to Muslims. The report stated that, generally, ordinary Muslim and Christian citizens enjoy good relations in contrast to the "strained" Jewish and Arab relations.[20] A 2005 BBC report also described Muslim and Christian relations as "peaceful".[124]

The Arab Human Rights Association, an Arab NGO in Israel, has stated that Israeli authorities have denied Palestinian Christians in Israel access to holy places, prevented repairs needed to preserve historic holy sites, and carried out physical attacks on religious leaders.[135]

Multiple factors, the internal dislocation of Palestinians in wars; the creation of three contiguous refugee camps for those displaced; emigration of Muslims from Hebron; hindrances to development under Israeli military occupation with its land confiscations, and a lax and corrupt judicial system under the PNA that is often incapable of enforcing laws, have all contributed to Christian emigration, which has been a tradition since the British Mandate period. This has been contested,[who?] as the main cause of Christian emigration from Bethlehem, Kairos Palestine—an independent coalition Christian organisation, set up to help communicate to the Christian world what is happening in Palestine—sent a letter to The Wall Street Journal to explain that "In the case of Bethlehem, for instance, it is in fact the rampant construction of Israeli settlements, the chokehold imposed by the separation wall and the Israeli government's confiscation of Palestinian land that has driven many Christians to leave," the unprinted letter, quoted in Haaretz, states. "At present, a mere 13 percent of Bethlehem-area land is left to its Palestinian inhabitants".[136]

Most of the Gaza Strip's Christian population lived in Gaza City, in the north.[137] In 2023 the Israeli militarily attempted to force them out by the Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip.[138] As of October 2024, most of Gaza's Christians had refused to leave, our not felt safe to traverse the war zone.[139] In November 2024, Israel announced that no Palestinians would be allowed to "return" to North Gaza.[140][141][142]

Persecutions

Majority of Palestinian Christians are leaving the territories due to the Arab-Israeli conflict.[143] There have been reports of attacks on Palestinian Christians in Gaza from Muslim extremist groups. Gaza Pastor Manuel Musallam has voiced doubts that those attacks were religiously motivated.[144]

Fr Pierbattista Pizzaballa, the Custodian of the Holy Land, a senior Catholic spokesman, has stated that police inaction and an educational culture that encourages Jewish children to treat Christians with "contempt" has made life increasingly "intolerable" for many Christians. Fr Pizzaballa's statement came after pro-settler extremists attacked a Trappist monastery in the town of Latroun, setting fire to its door, and covering walls with anti-Christian graffiti. The incident followed a series of acts of arson and vandalism, in 2012, targeting places of Christian worship, including Jerusalem's 11th century Monastery of the Cross, where slogans such as "Death to Christians" and other offensive graffiti were daubed on its walls. According to an article in the Telegraph, Christian leaders feel that the most important issue that Israel has failed to address is the practice of some ultra-Orthodox Jewish schools to teach children that it is a religious obligation to abuse anyone in Holy Orders they encounter in public, such that Ultra-Orthodox Jews, including children as young as eight, spit at members of the clergy on a daily basis.[145]

After Pope Benedict XVI's comments on Islam in September 2006, five churches of various denominations were firebombed and shot at in the West Bank and Gaza. A Muslim extremist group called "Lions of Monotheism" claimed responsibility.[146] Former Palestinian Prime Minister and Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh condemned the attacks, and police presence was elevated in Bethlehem, which has a sizable Christian community.[147]

Armenians in Jerusalem, identified as Palestinian Christians or Israeli-Armenians, have also been attacked and received threats from Jewish extremists; Christians and clergy have been spat at, and one Armenian Archbishop was beaten and his centuries-old cross broken. In September 2009, two Armenian Christian clergy were expelled after a brawl erupted with a Jewish extremist for spitting on holy Christian objects.[148]

In February 2009, a group of Christian activists within the West Bank wrote an open letter asking Pope Benedict XVI to postpone his scheduled trip to Israel unless the government changed its treatment.[149] They highlighted improved access to places of worship and ending the taxation of church properties as key concerns.[149] The Pope began his five-day visit to Israel and the Palestinian Authority on Sunday, 10 May, planning to express support for the region's Christians.[12] In response to Palestinian public statements, Israeli Foreign Ministry spokesman Yigal Palmor criticized the political polarization of the papal visit, remarking that "[i]t will serve the cause of peace much better if this visit is taken for what it is, a pilgrimage, a visit for the cause of peace and unity".[150]

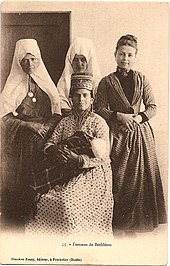

- Bethlehem

Christian families are the largest landowners in Bethlehem and have often been subject to theft of property. Bethlehem's core of traditional Christian and Muslim families speak of the rise of a 'foreign', more conservative, Islamic Hebronite class as changing the traditional regional identity of the town, as are the villages dominated by the Ta'amre Bedouin clans close to Bethlehem. Rising Muslim land purchase, said at times to be Saudi-financed, and incidents of land theft with forged documents, except in Beit Sahour where Christian and Muslims share a strong sense of local identity, are seen by Christians as making their demographic presence vulnerable. Christians are often described as of Yamani descent (as are some Muslim clans), vs the al-Qaysi Muslim clans, respectively from southern and northern Arabia. Christians are wary of the international media and of discussing these issues publicly, which involve criticism of fellow Palestinians, since there is a risk that their remarks may be manipulated by outsiders to undermine Palestinian claims to nationhood, distract attention from the crippling impact of Israel's occupation, and conjure up an image of a Muslim drive to oust Christians from Bethlehem.[151]

The Christian Broadcasting Network (an American Protestant organization) claimed that Palestinian Christians suffer systematic discrimination and persecution at the hands of the predominantly Muslim population and Palestinian government aimed at driving their population out of their homeland.[152] However, Palestinian Christians in Bethlehem and Beit Jala have claimed otherwise that it is the loss of agricultural land and expropriation from the Israeli military, the persecution of 1948 and violence from the military occupation that has led to a flight and major exodus of Christians.[153]

On 26 September 2015, the Mar Charbel monastery in Bethlehem was set on fire, resulting in the burning of many rooms and damaging various parts of the building.[154]

In September 2016, the Jerusalem-based Center for Jewish–Christian Understanding and Cooperation (CJCUC) established Blessing Bethlehem, a charity fundraising initiative with the purpose of helping the persecuted Christians living in the city of Bethlehem and its surrounding areas.[155]

See also

- List of Palestinian Christians

- Arab Christians

- Arab Orthodox Movement

- Demographic history of Palestine (region)

- Arab Christian citizens of Israel

- Christianity in Israel

References

- ^ Farsoun, Samih (2004). Culture and Customs of the Palestinians.

- ^ Bernard Sabella. "Palestinian Christians: Challenges and Hopes". Bethlehem University. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2004.

- ^ "The World Factbook". Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ IMEU. "Palestinian Christians in the Holy Land". Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Report to the League of Nations on Palestine and Transjordan, 1937". British Government. 1937. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ Jewish Council for Public Affairs. "JCPA Background Paper on Palestinian Christians" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Chronicles – Volume 26. Rockford Institute. 2002. p. 7.

- ^ The Palestinian Diaspora, p. 43, Helena Lindholm Schulz, 2005

- ^ "Palestinian Genes Show Arab, Jewish, European and Black-African Ancestry". Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ Freas, Erik (2016). Muslim-Christian Relations in Late Ottoman Palestine, Where Nationalism and Religion Intersect. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-1-137-57041-3.

- ^ Lance D.Laird,'Boundaries and Baraka: Christians, Muslims, and a Palestinian Saint,' in Margaret Cormack (ed.), Muslims and Others in Sacred Space, Archived 1 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine Oxford University Press, 2013 pp. 40–73, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e f "FACTBOX – Christians in Israel, West Bank and Gaza". Reuters. 10 May 2009. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Israel denies Gaza Christians permits to celebrate Christmas with families". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ "Population of Palestine". Fanack.com. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ "Opinion: They're Palestinians, not 'Israeli Arabs'". Los Angeles Times. 27 March 2015. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ "Arab Israeli Village Celebrates Chechnya Roots". The Forward. Archived from the original on 11 April 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b Sabella, Bernard (12 February 2003). "Palestinian Christians: Challenges and Hopes". Al-Bushra. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ a b J. B. Barron, ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine. Tables XII–XVI.

- ^ Palestine Census (1922).

- ^ a b c "Israel and the Occupied Territories". 2001-2009.state.gov. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ Meron Rapoport (11 February 2007). "Government's precondition for Orthodox patriarch's appointment: 'Sell church property only to Israelis'". Archived from the original on 18 December 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ "Jerusalem affairs: Religiously political". The Jerusalem Post. 20 December 2007. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Patriarch Pizzaballa takes possession of See of Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem". Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem. 6 November 2020. Archived from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ See, Come and. "Suheil Dawani enthroned as Anglican Bishop of Jerusalem". Come And See. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ Hadeel Al Gherbawi (21 December 2021). "Gaza's few Christians lift economy". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ God's Human Face: The Christ-Icon by Christoph Schoenborn 1994 ISBN 0-89870-514-2 p. 154

- ^ Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine by John Galey 1986 ISBN 977-424-118-5 p. 92

- ^ Theissen, G (1978). Sociology of early Palestinian Christianity. Fortress Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8006-1330-3. Archived from the original on 19 November 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d Thomas, D. R. (2001). Syrian Christians under Islam: The First Thousand Years. Leiden: Brill. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-90-04-12055-6.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Yizhar (2004). "The monasteries of Gaza: An archaeological review". In Brouria Bitton-Ashkelony; Aryeh Kofsky (eds.). Christian Gaza in Late Antiquity. Brill. pp. 61–62, 87. ISBN 9789004138681. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ^ Masalha, Nur (2016). "The Concept of Palestine: The Conception Of Palestine from the Late Bronze Age to the Modern Period". Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. 15 (2): 143–202. doi:10.3366/hlps.2016.0140. ISSN 2054-1988. Archived from the original on 4 November 2023. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

In the mid-7th century the population of Palestine was predominantly Christian, mostly Palestinian Aramaic-speaking Christian peasants who continued to speak the language of Jesus under Islam.

- ^ Bowersock, G. W.; Brown, Peter; Grabar, Oleg (1998). Late Antiquity: A guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674511705.

Late Antiquity - Bowersock/Brown/Grabar.

- ^ Noble, Samuel; Treiger, Alexander (15 March 2014). The Orthodox Church in the Arab World, 700–1700: An Anthology of Sources. Cornell University Press. pp. 160–162. ISBN 978-1-5017-5130-1. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Tramontana, Felicita (2014). "Chapter I "Christians in Seventeenth-century Palestine"". Passages of Faith: Conversion in Palestinian villages (17th century) (1 ed.). Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 24–25. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc16s06.6. ISBN 978-3-447-10135-6. JSTOR j.ctvc16s06. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Bernard Regan (30 October 2018). The Balfour Declaration: Empire, the Mandate and Resistance in Palestine. Verso Books. p. 57.

- ^ Laura Robson, Colonialism and Christianity in Mandate Palestine, University of Texas Press, 2011 p. 159

- ^ Rashid Khalidi (9 January 2006). The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood. Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807003084. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

rashid khalidi the iron cage.

- ^ Kayyali, Abdul-Wahhab Said (1981). Palestine: A Modern History. Croom Helm. ISBN 086199-007-2.

- ^ Ben-Zvi, Itzhak (1967). שאר ישוב: מאמרים ופרקים בדברי ימי הישוב העברי בא"י ובחקר המולדת [She'ar Yeshuv] (in Hebrew). תל אביב תרפ"ז. pp. 409–410.

- ^ Nur Masalha, Lisa Isherwood, Theologies of Liberation in Palestine-Israel: Indigenous, Contextual, and Postcolonial Perspectives, Archived 1 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine The Lutterworth Press, 2014 pp. 21–22

- ^ Motti Golani, Adel Manna, Two Sides of the Coin: Independence and Nakba 1948, Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Institute for Historical Justice and Reconciliation, 2011 pp. 120, 130

- ^ Laura Robson, Colonialism and Christianity in Mandate Palestine, p. 162

- ^ a b c d Derfner, Larry (7 May 2009). "Persecuted Christians?". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ^ Jonathan Adelman and Agota Kuperman (24 May 2006). "The Christian Exodus from the Middle East" (PDF). Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2006. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- ^ Shelah, Ofer (29 May 2006). "Jesus and the Separation Fence". Ynet. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- ^ Robert Novak (25 May 2006). "Plea for Palestinian Christians". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 April 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2007. Reprinted at 'Churches for Middle East'.

- ^ Flower, Kevin (9 December 2009). "Israel court: Deported Palestinian student can't return". CNN News. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ TLV1 (21 January 2016). "Israeli-Arab Christians take to the streets of Haifa for an unusual protest". TLV1 RADIO. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Christians in Israel: A minority within a minority". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- ^ "Israel's Christian Awakening". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ "المسيحيون العرب يتفوقون على يهود إسرائيل في التعليم". Bokra. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ "וואלה! חדשות". וואלה! חדשות. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ "An inside look at Israel's Christian minority". Arutz Sheva. 24 December 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "Christian Arabs top country's matriculation charts". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ a b c Druckman, Yaron (20 June 1995). "Christians in Israel: Strong in education – Israel News, Ynetnews". Ynetnews. Ynet. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ 'Israel's Palestinian schools strike in support of Christians,' Archived 11 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Ma'an News Agency 7 September 2015.

- ^ "חדשות – בארץ nrg – ...המגזר הערבי נוצרי הכי מצליח במערכת". Nrg.co.il. 25 December 2011. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ a b Jonathan Lis (17 September 2014). "Israel recognizes Aramean minority in Israel as separate nationality". Archived from the original on 17 September 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ Knell, Yolande (22 January 2023). "First woman pastor in Holy Land ordained". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Two Christian women killed by IDF sniper fire, says Latin Patriarchate". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 18 December 2023. Archived from the original on 28 June 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ "Two women killed in Israeli attack on Holy Family parish in Gaza - Vatican News". www.vaticannews.va. 16 December 2023. Archived from the original on 24 December 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ Wagner, Don (12 March 2002). "Palestinian Christians: An Historic Community at Risk?". Al-Bushra. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Cohen, Hillel (2008). Army of shadows: Palestinian collaboration with Zionism, 1917 - 1948. Berkeley, Calif.: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25989-8.

- ^ "Palestine Who's Who (C-M)". Arab Gateway. Archived from the original on 21 April 2007.

- ^ Reich, Bernard (1990). Political Leaders of the Contemporary Middle East and North Africa: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 528. ISBN 978-0-313-26213-5.

- ^ MacLeod/Cairo, Scott (28 January 2008). "Terrorism's Christian Godfather". TIME. Archived from the original on 9 July 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ "George Habash". Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question. Archived from the original on 6 July 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Thomas Riegler (2020). "When modern terrorism began The OPEC hostage taking of 1975". In Dag Harald Claes; Giuliano Garavini (eds.). Handbook of OPEC and the Global Energy Order. Past, Present and Future Challenges (PDF). London: Routledge. p. 291. doi:10.4324/9780429203190. ISBN 9780429203190. S2CID 211416208.

- ^ Mark Ensalaco (2008). Middle Eastern Terrorism: From Black September to September 11. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8122-4046-7. JSTOR j.ctt3fhmb0. Archived from the original on 18 December 2023. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Jenkins, Philip. "Did You Know that the Radicals of the Middle East Used to Be Christians?". History News Network. Archived from the original on 9 July 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ "Convicted RFK assassin Sirhan Sirhan seeks prison release". CNN. 26 November 2011. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Martinez, Michael (1 March 2011). "Sirhan Sirhan, convicted RFK assassin, to face parole board". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Sirhan Sirhan: Biography". 6 November 2019. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Mel Ayton. "The Robert Kennedy Assassination: Unraveling the Conspiracy Theories". Crime Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010.

- ^ David Clay Large (2012). Munich 1972: Tragedy, Terror, and Triumph at the Olympic Games. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742567399.

- ^ "Indiana Spielberg and His Jewish Problem". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ Fogelman, Shay (31 August 2012). "תחקיר נרחב חושף פרטים חדשים על טבח מינכן" [Wide-ranging investigation reveals new details about the Munich Massacre]. Haaretz (in Hebrew). Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Large, David Clay (2012). Munich 1972: Tragedy, Terror, and Triumph at the Olympic Games. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-6739-9. Archived from the original on 9 July 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Germany and Israel: Whitewashing and Statebuilding. Oxford University Press. 30 March 2020. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-19-754000-8.

- ^ Black, Ian; Morris, Benny (1991). Israel's secret wars: a history of Israel's intelligence services. New York: Grove Weidenfeld. ISBN 978-0-8021-1159-3.

- ^ Sylas, Eluma Ikemefuna (2006). Terrorism: A Global Scourge. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4259-0530-9. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Benveniśtî, Mêrôn (2000). Sacred landscape: the buried history of the Holy Land since 1948. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23422-2. pp. 325–326.

- ^ "Justice for Ikrit and Biram" Archived 12 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Haaretz, 10 October 2001.

- ^ Elias Chacour with David Hazard: Blood Brothers: A Palestinian Struggles for Reconciliation in the Middle East. ISBN 978-0-8007-9321-0. Foreword by Secretary James A. Baker III. 2nd Expanded ed. 2003. pp. 44–61.

- ^ "اختطفت طائرة على متنها 140 إسرائيلياً.. من هي تيريزا هلسة التي كادت أن تردي نتنياهو قتيلاً؟". عربي بوست — ArabicPost.net. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ البرغوثي, نسرين نعيم. "خطفت طائرة في عمر الـ 18.. من هي تيريزا هلسة؟". الجزيرة نت (in Arabic). Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ محمود ■القاهرة, خالد (2 April 2020). "تيريزا هلسا.. فلسطينية أطلقت النار على نتنياهو". www.emaratalyoum.com (in Arabic). Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Palestinians Mourn Theresa Halsa, Hijacker of 1972 Flight to Tel Aviv". english.aawsat.com. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "وفاة المناضلة تيريزا هلسة إحدى منفذات "عملية اللد"". فلسطين أون لاين (in Arabic). 28 March 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Therese Halasa". Faces Of Palestine. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ a b Miskin, Maayana (5 July 2009). "PA Minister: Muslims, Christians Fighting Jews Together". Arutz Sheva. Israel. Archived from the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ "PA minister visits family of imprisoned Palestinian Christian". Ma'an News Agency. Palestinian Territories. 4 July 2009. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ "Israel warns of Iraq war 'earthquake'". BBC. 7 February 2003. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Israel Arrests Suspected Christian Palestinian Terrorist". www.catholicculture.org. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "First Christian in Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades". www.comeandsee.com. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ Ajbaili, Mustapha (18 October 2011). "Palestinian female prisoners resist deportation to Gaza". Al Arabiya News.

- ^ "Senior Tanzim operative killed during arrest activity in Bethlehem". embassies.gov.il. 23 April 2006. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ "Palestinian priests and mourners pray over the body of Daniel Abu Hamama..." Getty Images. 21 September 2023. Archived from the original on 9 July 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ "Fatah Martyr Daniel Saba George". The Palestine Poster Project Archives. 1 September 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ Katz, Itamar; Kark, Ruth (4 November 2005). "The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem and Its Congregation: Dissent over Real Estate". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 37 (4). Cambridge University Press: 509–534. doi:10.1017/S0020743805052189. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 3879643. S2CID 159569868. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Robson 2011, p. 77.

- ^ Haiduc-Dale, Noah (2013). Arab Christians in British Mandate Palestine: Communalism and Nationalism, 1917-1948. Edinburgh University Press. p. 174. doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9780748676033.001.0001. ISBN 9780748676033. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ Neveu, Norig (2021). "Orthodox Clubs and Associations: Cultural, Educational and Religious Networks Between Palestine and Transjordan, 1925–1950". In Sanchez Summerer, Karène; Zananiri, Sary (eds.). European Cultural Diplomacy and Arab Christians in Palestine, 1918–1948: Between Contention and Connection. Palgrave Macmillan Cham. pp. 37–62. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-55540-5_3. ISBN 978-3-030-55539-9. S2CID 229454185.

- ^ Miller, Duane Alexander (April 2014). "Freedom of Religion in Israel-Palestine: may Muslims become Christians, and do Christians have the freedom to welcome such converts?". St Francis Magazine. 10 (1): 17–24. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ "About Sabeel". Archived from the original on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ "sabeel.org". Archived from the original on 5 May 2007. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ a b Jacob Edelist (3 July 2012). "Report: Western Governments Fund Anti-Israel Church Activism". The Jewish Press. Archived from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "The Debate on Jew-washing – Beyond the Ideology". The Daily Beast. 13 August 2012. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Fink, Daniel (26 October 2007). "Sabeel's 'Peace' façade". Ynetnews. Ynet. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Updating the Ancient Infrastructure of Christian Contempt". Jerusalem Center For Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Ateek, Na'em S. (1982). "Toward a Strategy for the Episcopal Church in Israel with Special Focus on ... – Na'em S. Ateek – Google Books". Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Lowe, Malcolm (April 2010). "The Palestinian Kairos Document: A Behind-the-Scenes Analysis". New English Review. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Qumsiyeh, Mazin (25 December 2009). "16 Christian Leaders Call for an End to the Israeli Occupation of Palestine". Al-Jazeerah: Cross-Cultural Understanding. ccun.org Archived 7 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Holy Land Christian Ecumenical Foundation". Charity Navigator. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Holy Land Christian Ecumenical Foundation (HCEF)". Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Holy Land Christian Ecumenical Foundation Volunteer Opportunities". Volunteer Match. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Asmaa al-Ghoul (18 April 2013). "Do Gaza's Christians Feel Safe?". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 5 November 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "Christians in Gaza: An Integral Part of Society". Asharq al-Awsat. 20 October 2007. Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ Saleh Jadallah (26 July 2012). "Gaza Christians, Hamas at Odds Over Conversions to Islam". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 5 November 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "Holy Family School in Gaza is growing". Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 10 February 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Gaza Christians Observe Somber Christmas after Murder". 25 December 2007. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Rizq, Philip (15 October 2007). "The murder of Rami Ayyad". Palestine Chronicle. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Marsi, Federica (10 November 2023). "Gaza's Christian community faces 'threat of extinction' amid Israel war". Al-Jazeera. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ a b c "Guide: Christians in the Middle East". BBC. 15 December 2005. Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- ^ Ali Abunimah, One Country: A Bold Proposal to End the Israeli-Palestinian Impasse, Metropolitan Books 2006 p. 97.

- ^ Elaine C. Hagopian, ' Palestinian Refugee: Victims of Zionist Ideology,' in Maurine and Robert Tobin (ds.), How Long O Lord?: Christian, Jewish, and Muslim Voices from the Ground and Visions of the Future in Israel/Palestine, Cowley Publications 2003 pp. 29–50, 36–37.

- ^ Masalha, Nur (1996). "An Israeli Plan to Transfer Galilee's Christians to South America: Yosef Weitz and "Operation Yohanan," 1949–53". CMEIS Occasional Paper. Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, University of Durham. ISSN 1357-7522.

- ^ Sharp, Heather (22 December 2005). "Bethlehem's Christians cling to hope". BBC News. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- ^ "Israeli-Palestinian conflict blamed for Christian exodus". The Jerusalem Post. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Habibi, Emile (2006). Saraya, the Ogre's Daughter: A Palestinian Fairy Tale. Ibis Editions. p. 169.

- ^ Matthew Kalman in Beit Jala (12 April 2011). "The ravaged palace that symbolises the hope of peace". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ 'You See How Many We Are!'. David Adams lworldcommunication.org Archived 17 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Palestine in South America. V!VA Travel Guides. vivatravelsguides.com Archived 18 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Americans not sure where Bethlehem is, survey shows". Ekklesia. 20 December 2006. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- ^ "Sanctity Denied: The Destruction and Abuse of and Christian Holy Places in Israel" (in Arabic). arabhra.org. Archived from the original on 23 February 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ^ "Christian Palestinians: Israel 'Manipulating Facts' by Claiming We Are Welcome". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 20 August 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Tulloch, Joseph. "Palestinian Christians despair as Gaza homeland destroyed by Israel's war". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ "Why displaced Palestinians in northern Gaza fear they won't be able to return to their homes". SBS News. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ Sudilovsky, Judith. "In the 'bleeding region,' Gaza Strip's Christian community lifts each other up, defying reality". www.ncronline.org. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ Kubovich, Yaniv. "'There will be no return': IDF says it won't allow residents to return to northern Gaza". Haaretz.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ McKernan, Bethan; Christou, William (6 November 2024). "Palestinians will not be allowed to return to homes in northern Gaza, says IDF". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ "Palestinians not allowed to return home to Northern Gaza: IDF". ABC listen. 7 November 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (2 May 2019). "Persecution of Christians 'coming close to genocide' in Middle East – report". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ Musallam, Manuel (27 November 2007). "Christians And Muslims Coexist in Gaza". IPS news. ipsnews.net Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Blomfield, Adrian (7 September 2012). "Vatican official says Israel fostering intolerance of Christianity". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Report: Rome tightens pope's security after fury over Islam remarks" Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Haaretz, 16 September 2006

- ^ Fisher, Ian (17 September 2006). "Pope Apologizes for Remarks About Islam". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 December 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ Hagopian, Arthur (9 September 2009). "Armenian Patriarchate protests deportation of seminarians". uruknet.de Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Holy Land Christians urge pope to call off visit[dead link]. MSNBC.com. Published 22 February 2009.

- ^ "Palestinians seek papal pressure on Israel". The Guardian. London. 8 May 2009. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ^ Bård Kårtveit, 'Land, Law and Family Protection in the West Bank,' in Anh Nga Longva, Anne Sofie Roald (eds.),Religious Minorities in the Middle East: Domination, Self-Empowerment, Accommodation, Archived 1 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine Brill, 2011 pp. 97–121, esp. pp. 116f.

- ^ "Why Are Christians Really Leaving Bethlehem?". CBN. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Lonely This Christmas A Glimpse Into the Life of the West Bank's Last Christians Archived 22 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Dina Kraft, 26 Dec 2017, Haaretz

- ^ "Bethlehem: Mar Charbel Monastery set on fire". Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ ELI POLLAK, YISRAEL MEDAD (28 September 2018). "MEDIA COMMENT: THE POSITIVE SIDE". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

Further reading

- Morris, Benny, 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War, (2009) Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15112-1

- Reiter, Yitzhak, National Minority, Regional Majority: Palestinian Arabs Versus Jews in Israel (Syracuse Studies on Peace and Conflict Resolution), (2009) Syracuse Univ Press (Sd). ISBN 978-0-8156-3230-6

- Robson, Laura (2011). Colonialism and Christianity in Mandate Palestine. University of Texas Press. doi:10.7560/726536. ISBN 978-0-292-72653-6.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (January 2023) |

- Palestinian Christians in the Holy Land and the Diaspora. Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem, 21 October 2014

- Palestinian Christians in the Holy Land. Institute for Middle East Understanding, 17 December 2012

- Christian Presence in Palestine and the Diaspora: Statistics, Challenges and Opportunities Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Global Ministries, 31 August 2012

- Middle East Christians: Gaza pastor (Interview with Hanna Massad). BBC News. Published 21 December 2005.

- Christians in the Middle East – 11 May 09 – Part 1 – Riz Khan on YouTube at Al Jazeera English

- Christians in the Middle East – 11 May 09 – Part 2 – Riz Khan on YouTube at Al Jazeera English

- Bethlehem University

- "What is it like to be a Palestinian Christian?" at Beliefnet.com

- Religion in the news – Israelis and Palestinians

- Hard Time in the House of Bread

- Al-Bushra Archived 1 April 2004 at the Wayback Machine (an Arab-American Catholic perspective)

- Palestinian Christians: Challenges and Hopes by Bernard Sabella

- Salt of the Earth: Palestinian Christians in the Northern West Bank, a documentary film series

- Arab Christians in Israel threaten to close their churches. MEMO, 28 September 2015