Leaning Tower of Pisa

| Leaning Tower of Pisa | |

|---|---|

Torre pendente di Pisa | |

Leaning Tower of Pisa in 2022 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic Church |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Pisa, Italy |

| Geographic coordinates | 43°43′23″N 10°23′47″E / 43.72306°N 10.39639°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Diotisalvi (?) Bonanno Pisano (?) |

| Style | Romanesque |

| Groundbreaking | 1173 |

| Completed | 1372 |

| Specifications | |

| Height (max) | 55.86 m (183 ft 3 in) |

| Materials | |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Part of | Piazza del Duomo, Pisa |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 395 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

The Leaning Tower of Pisa (Italian: torre pendente di Pisa [ˈtorre penˈdɛnte di ˈpiːza, - ˈpiːsa][1]), or simply the Tower of Pisa (torre di Pisa), is the campanile, or freestanding bell tower, of Pisa Cathedral. It is known for its nearly four-degree lean, the result of an unstable foundation. The tower is one of three structures in Pisa's Cathedral Square (Piazza del Duomo), which includes the cathedral and Pisa Baptistry.

The height of the tower is 55.86 metres (183 feet 3 inches) from the ground on the low side and 56.67 m (185 ft 11 in) on the high side. The width of the walls at the base is 2.44 m (8 ft 0 in). Its weight is estimated at 14,500 tonnes (16,000 short tons).[2] The tower has 296 or 294 steps; the seventh floor has two fewer steps on the north-facing staircase.

The tower began to lean during construction in the 12th century, due to soft ground which could not properly support the structure's weight. It worsened through the completion of construction in the 14th century. By 1990, the tilt had reached 5.5 degrees.[3][4][5] The structure was stabilized by remedial work between 1993 and 2001, which reduced the tilt to 3.97 degrees.[6]

Architect

The identity of the architect of the tower is a subject of controversy. The design had long been attributed to a man named Guglielmo and to Bonanno Pisano, the latter a well-known 12th-century resident artist of Pisa known for his bronze casting, particularly in the Pisa Duomo.[7][better source needed] Pisano left Pisa in 1185 for Monreale, Sicily, only to return and die in his home town. A piece of cast bearing his name was discovered at the foot of the tower in 1820, but this may be related to the bronze door in the façade of the cathedral that was destroyed in 1595. A 2001 study seems to indicate Diotisalvi was the original architect, due to the time of construction and affinity with other Diotisalvi works, notably the bell tower of San Nicola and the Baptistery, both in Pisa.[8][page needed]

-

Column capital details on top level

-

Column details

-

Base wall columns

-

Flower pendant

-

Entrance

-

Wall relief details of animals

-

Outer floor tiles

-

Assunta bell

-

Pasquareccia bell

-

Top-level bells

Construction

Construction of the tower occurred in three stages over 199 years. On 5 January 1172, Donna Berta di Bernardo, a widow and resident of the house of dell'Opera di Santa Maria, bequeathed sixty soldi to the Opera Campanilis petrarum Sancte Marie. The sum was then used toward the purchase of a few stones which still form the base of the bell tower.[9] On 9 August 1173, the foundations of the tower were laid.[10] Work on the ground floor of the white marble campanile began on 14 August of the same year during a period of military success and prosperity. This ground floor is a blind arcade articulated by engaged columns with classical Corinthian capitals.[11] Nearly four centuries later Giorgio Vasari wrote: "Guglielmo, according to what is being said, in the year 1174, together with sculptor Bonanno, laid the foundations of the bell tower of the cathedral in Pisa".[12]

The tower began to sink after construction had progressed to the second floor in 1178. This was due to a mere three-metre foundation, set in weak, unstable subsoil, a design that was flawed from the beginning. Construction was subsequently halted for the better part of a century, as the Republic of Pisa was almost continually engaged in battles with Genoa, Lucca, and Florence. This allowed time for the underlying soil to settle. Otherwise, the tower would almost certainly have toppled.[13] On 27 December 1233, the worker Benenato, son of Gerardo Bottici, oversaw the continuation of the tower's construction.[14]

On 23 February 1260, Guido Speziale, son of Giovanni Pisano, was elected to oversee the building of the tower.[15] On 12 April 1264, the master builder Giovanni di Simone, architect of the Camposanto, and 23 workers went to the mountains close to Pisa to cut marble. The cut stones were given to Rainaldo Speziale, worker of St. Francesco.[16] In 1272, construction resumed under Di Simone. In an effort to compensate for the tilt, the engineers built upper floors with one side taller than the other. Because of this, the tower is curved.[17] Construction was halted again in 1284 when the Pisans were defeated by the Genoese in the Battle of Meloria.[10][18]

The seventh floor was completed in 1319.[19] The bell-chamber was finally added in 1372. It was built by Tommaso di Andrea Pisano, who succeeded in harmonizing the Gothic elements of the belfry with the Romanesque style of the tower.[20][21] There are seven bells, one for each note of the musical major scale. The largest one was installed in 1655.[13]

History following construction

Between 1589 and 1592,[22] Galileo Galilei, who lived in Pisa at the time, is said to have dropped two cannonballs of different masses from the tower to demonstrate that their speed of descent was independent of their mass, in keeping with the scientific law of free fall. The primary source for this is the biography Racconto istorico della vita di Galileo Galilei (Historical Account of the Life of Galileo Galilei), written by Galileo's pupil and secretary Vincenzo Viviani in 1654, but only published in 1717, long after his death.[23][24]

During World War II, the Allies suspected that the Germans were using the tower as an observation post. Leon Weckstein, a U.S. Army sergeant sent to confirm the presence of German troops in the tower, was impressed by the beauty of the cathedral and its campanile, and thus refrained from ordering an artillery strike, sparing it from destruction.[25][26]

Numerous efforts have been made to restore the tower to a vertical orientation or at least keep it from falling over. Most of these efforts failed; some worsened the tilt. On 27 February 1964, the government of Italy requested aid in preventing the tower from toppling. It was, however, considered important to retain the current tilt, due to the role that this element played in promoting the tourism industry of Pisa.[27]

Starting in 1993, 870 tonnes of lead counterweights were added, which straightened the tower slightly.[28]

The tower and the neighbouring cathedral, baptistery, and cemetery are included in the Piazza del Duomo UNESCO World Heritage Site, which was declared in 1987.[29]

The tower was closed to the public on 7 January 1990,[30] after more than two decades of stabilisation studies and spurred by the abrupt collapse of the Civic Tower of Pavia in 1989.[31][32] The bells were removed to relieve some weight, and cables were cinched around the third level and anchored several hundred meters away, and residences in the path of a potential collapse were vacated. The selected method for preventing the collapse of the tower was to slightly reduce its tilt to a safer angle by removing 38 cubic metres (1,342 cubic feet) of soil from underneath the raised end. The tower's tilt was reduced by 45 centimetres (17+1⁄2 inches), returning to its 1838 position. After a decade of corrective reconstruction and stabilization efforts, the tower was reopened to the public on 15 December 2001, and was declared stable for at least another 300 years.[28] In total, 70 metric tons (77 short tons) of soil were removed.[33]

After a phase (1990–2001) of structural strengthening,[34] the tower has been undergoing gradual surface restoration to repair visible damage, mostly corrosion and blackening. These are particularly pronounced due to the tower's age and its exposure to wind and rain.[35] In May 2008, engineers announced that the tower had been stabilized such that it had stopped moving for the first time in its history. They stated that it would be stable for at least 200 years.[33]

A ceremony for the 850th anniversary of the laying of the foundation stone was held on 9 August 2023.[36]

-

Leaning Tower of Pisa in the 1890s[37]

-

Plaque in memory of Galileo Galilei's experiments

-

Temporary lead counterweights, 1998

-

The Baptistery (in the foreground), the Cathedral (in the middleground), and the Leaning Tower of Pisa (in the background)

Earthquake survival

The tower has survived at least four strong earthquakes since 1280. A 2018 engineering investigation concluded that the tower withstood the tremors because of dynamic soil-structure interaction: the height and stiffness of the tower combined with the softness of the foundation soil influences the tower's vibrational characteristics in such a way that it does not resonate with earthquake ground motion. The same soft soil that caused the leaning and brought the tower to the verge of collapse helped it survive.[38]

Technical information

- Elevation of Piazza del Duomo: about 2 metres (6 feet, DMS)

- Height from the ground floor: 55.863 m (183 ft 3+5⁄16 in),[39] 8 stories[40]

- Height from the foundation floor: 58.36 m (191 ft 5+1⁄2 in)[41]

- Outer diameter of base: 15.484 m (50 ft 9+5⁄8 in)[39]

- Inner diameter of base: 7.368 m (24 ft 2+1⁄16 in)[39]

- Angle of slant: 3.97 degrees[42] or 3.9 m (12 ft 10 in) from the vertical[43]

- Weight: 14,700 metric tons (16,200 short tons)[44]

- Thickness of walls at the base: 2.44 m (8 ft 0 in)

- Total number of bells: 7, tuned to musical scale,[45] clockwise:[citation needed]

- 1st bell: L'Assunta, cast in 1654 by Giovanni Pietro Orlandi, weight 3,620 kg (7,981 lb)

- 2nd bell: Il Crocifisso, cast in 1572 by Vincenzo Possenti, weight 2,462 kg (5,428 lb)

- 3rd bell: San Ranieri, cast in 1719–1721 by Giovanni Andrea Moreni, weight 1,448 kg (3,192 lb)

- 4th bell: La Terza (1st small one), cast in 1473, weight 300 kg (661 lb)

- 5th bell: La Pasquereccia or La Giustizia, cast in 1262[46] by Lotteringo, weight 1,014 kg (2,235 lb)

- 6th bell: Il Vespruccio (2nd small one), cast in the 14th century and again in 1501 by Nicola di Jacopo, weight 1,000 kg (2,205 lb)

- 7th bell: Dal Pozzo, cast in 1606 and again in 2004, weight 652 kg (1,437 lb)[47]

- Number of steps to the top: 296[48]

About the 5th bell: The name Pasquareccia comes from Easter, because it used to ring on Easter day. However, this bell is older than the bell-chamber itself, and comes from the tower Vergata in Palazzo Pretorio in Pisa, where it was called La Giustizia (The Justice). The bell was tolled to announce executions of criminals and traitors, including Count Ugolino in 1289.[49] A new bell was installed in the bell tower at the end of the 18th century to replace the broken Pasquareccia.[citation needed]

The circular shape and great height of the campanile were unusual for their time, and the crowning belfry is stylistically distinct from the rest of the construction. This belfry incorporates a 14 cm (5+1⁄2 in) correction for the inclined axis below. The siting of the campanile within the Piazza del Duomo diverges from the axial alignment of the cathedral and baptistery of the Piazza del Duomo.[citation needed]

Guinness World Records

Two German churches have challenged the tower's status as the world's most lopsided building: the 15th-century square Leaning Tower of Suurhusen and the 14th-century bell tower in the town of Bad Frankenhausen.[50] Guinness World Records measured the Pisa and Suurhusen towers, finding the former's tilt to be 3.97 degrees.[42] In June 2010, Guinness World Records certified the Capital Gate building in Abu Dhabi, UAE as the "World's Furthest Leaning Man-made Tower";[51] it has an 18-degree slope, almost five times more than the Tower of Pisa, but was deliberately engineered to slant. The Leaning Tower of Wanaka in Wānaka, New Zealand, also deliberately built, leans at 53 degrees to the ground.[52]

Gallery

-

View looking up

-

Entrance door to the bell tower

-

External loggia

-

Inner staircase from sixth to seventh floor

-

Inner staircase from seventh to eighth (the top) floor

-

View from the top

-

View, looking down from the top

-

Leaning Tower of Pisa in 2013

-

Tourist in a common pose at Tower of Pisa, June 2009

See also

- Leaning Temple of Huma

- List of leaning towers

- Leaning Tower of Niles, a replica of the Tower of Pisa

- Leaning Tower of Zaragoza, was a famous European leaning tower

- Great Mosque of al-Nuri (Mosul), an ancient leaning tower that stood until 2017; reconstruction efforts are currently underway

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

- Round tower (disambiguation), for other types of round towers

- The Greyfriars Tower, the remains of a Franciscan monastery in King's Lynn, nicknamed "The Leaning Tower of Lynn"

- Torre delle Milizie, a tilting medieval tower in Rome

- Tour de Pise, a rock dome in Antarctica, was named after this tower

References

- ^ "DiPI Online". Dizionario di Pronuncia Italiana (in Italian). Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Leaning Tower of Pisa Facts". Leaning Tower of Pisa. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ^ "Europe | Saving the Leaning Tower". BBC News. 15 December 2001. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

- ^ "Tower of Pisa". Archidose.org. 17 June 2001. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Leaning Tower of Pisa (tower, Pisa, Italy)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

- ^ "Leaning tower of Pisa loses crooked crown". Irish News. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ "Endex.com". www.endex.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007.

- ^ Pierotti, Piero. (2001). Deotisalvi – L'architetto pisano del secolo d'oro. Pisa: Pacini Editore

- ^ Capitular Record Offices of Pisa, parchment n. 248

- ^ a b Potts, David M.; Zdravković, Lidija (2001). Finite Element Analysis in Geotechnical Engineering: Application. Thomas Telford. p. 254. ISBN 9780727727831. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ Toy, Sidney (1920). "The Campanile of Pisa". Indian Engineerion. 68 – via Google Books.

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio (1878). Le opere di Giorgio Vasari: Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori (in Italian). G.C. Sansoni. pp. 274. OCLC 15220635.

Guglielmo, secondo che si dice, l'anno 1174, insieme con Bonanno scultore, fondò in Pisa il campanile del Duomo, dove sono alcune parole

- ^ a b "Fall of the Leaning Tower – History of Interventions". NOVA Online (PBS). 1999. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Public Record Offices of Pisa, Opera della Primaziale, 27 December 1234

- ^ Public Record Offices of Pisa, Opera della Primaziale, 23 February 1260

- ^ Public Record Offices of Pisa, Roncioni, 12 April 1265.

- ^ McLain, Bill (1999). Do Fish Drink Water?. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc. pp. 291–292. ISBN 0688165125.

- ^ Touring club italiano (2005). Authentic Tuscany. Touring Editore. p. 64. ISBN 9788836532971. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ Roth, Leland M. (2018). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History, and Meaning. Routledge. p. 98. ISBN 9780429975219. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ G. Barsali (1999), Pisa. History and masterpieces, Bonechi, p. 18, ISBN 8872041880, archived from the original on 9 August 2021, retrieved 25 August 2015

- ^ Giorgio Vasari, Jean Paul Richter (1855), Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, H. G. Bohn, p. 153, archived from the original on 9 August 2021, retrieved 14 November 2020

- ^ Some contemporary sources speculate about the exact date; e.g. Rachel Hilliam gives 1591 (Galileo Galilei: Father of Modern Science, The Rosen Publishing Group, 2005, p. 101).

- ^ "Sci Tech: Science history: setting the record straight". The Hindu. 30 June 2005. Archived from the original on 2 November 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Vincenzo Viviani Archived 6 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine on museo galileo

- ^ Shrady, Nicholas (7 October 2003). Tilt: a skewed history of the Tower of Pisa. Simon & Schuster. pp. 147–152. ISBN 978-0-74-322926-5. OCLC 52086370. Retrieved 28 September 2023 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Why I spared the Leaning Tower of Pisa". The Guardian. 12 January 2000. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ "Securing the Lean In Tower of Pisa". The New York Times. 1 November 1987. Archived from the original on 14 February 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Tipping the Balance". TIME Magazine. 25 June 2001. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Piazza del Duomo, Pisa". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "BBC on this day: 1990: Leaning Tower of Pisa closed to public". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Hofman, Paul (30 July 1989). "Italy's Endangered Treasures". New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Montalbo, William D (18 March 1989). "900-Year-Old Bell Tower Collapses in Italy; Three Killed". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b Duff, Mark (28 May 2008). "Europe | Pisa's leaning tower 'stabilised'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ A profile of an engineer employed to straighten the tower Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Ingenia, March 2005

- ^ "Restoration work is mentioned at the official website of the square". Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 14 May 2007.

- ^ "La Torre Pendente di Pisa compie 850 anni". tgcom24.mediaset.it. tgcom24.mediaset.it. 8 August 2023. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ Tom (6 May 2015). "Leaning Tower of Pisa in the 1890s". Cool Old Photos. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ "500-year-old Leaning Tower of Pisa mystery unveiled by engineers". ScienceDaily. 9 May 2018. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ a b c "2051?". The Michigan Architect and Engineer. 27: 17. 1952. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ Burland, J.B. (2008). "Stabilising the Leaning Tower of Pisa: the Evolution of Geotechnical Solutions". Trans. Newcomen Soc. 78 (2): 174. doi:10.1179/175035208X317657. ISSN 0372-0187. S2CID 110178919.

- ^ Valdes, Giuliano (1994). Art and History of Pisa. Casa Editrice Bonechi. p. 44. ISBN 9788880290247. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ a b "German steeple beats Leaning Tower of Pisa into Guinness book". Trend News Agency. AFP. 9 November 2007. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009.

- ^ tan(3.97 degrees) * (55.86m + 56.70m)/2 = 3.9m

- ^ Strom, Steven; Nathan, Kurt; Woland, Jake; Lamm, David (2009). Site Engineering for Landscape Architects. John Wiley and Sons. p. 124. ISBN 9780471695493. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ Black, William Harman (1920). The Real Europe Pocket Guide-book: Number 10 of the 'Black's Blue Books'. Brentanos. pp. 360. OCLC 316943604.

- ^ Black, Charles Bertram (1898). The Riviera, Or The Coast from Marseilles to Leghorn: Including the Interior Towns of Carrara, Lucca, Pisa and Pistoia. A. & C. Black. pp. 148. OCLC 18806463.

- ^ "Leaning Tower of Pisa: 1920s Photo of Dal Pozzo". www.endex.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ^ Davies, Andrew (2005). The Children's Visual World Atlas. Sydney, Australia: The Fog Press. ISBN 1740893174.

- ^ "Torre pendente" (in Italian). Lucca turismo. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- ^ Sunday Telegraph no. 2,406, 22 July 2007

- ^ "Not so fast, Pisa! UAE lays claim to world's furthest leaning tower". CNN news. 7 June 2010. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ 'Leaning and tumbling towers' Archived 30 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine on Puzzling World website, viewed 30 July 2011

External links

- Opera della Primaziale Pisana – official site (in English and Italian)

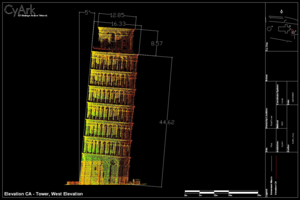

- Piazza dei Miracoli digital media archive (Creative Commons – licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas), data from a University of Ferrara/CyArk research partnership, includes 3D scan data from the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

- Leaning Tower of Pisa at Structurae

![Leaning Tower of Pisa in the 1890s[37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/Leaning_Tower_of_Pisa_in_the_1890s.jpg/357px-Leaning_Tower_of_Pisa_in_the_1890s.jpg)